Disability Writes

Fieldnotes on Writing, Teaching, and Embodiment

Author Archives: Andrew Lucchesi

Inauspicious Beginnings: Five Ws and an H

I hate first blog posts. I always feel pressure to get things started in just the right way: first posts should frame my project or my goals with foresight and ambition, should introduce myself in a voice that makes me sound fun and intelligent enough to keep your interest. First posts should be auspicious. This pile of shoulds freaks me out, and I usually end up procrastinating, fretting, over-thinking, and ultimately not writing. Shoulds are the adversaries of writing.

So, an inauspicious beginning is in order. Let’s see how prosaic I can be: just the facts.

Who (am I)?

My name’s Andrew Lucchesi. I am a PhD student at the City University of New York Graduate Center, where I’m working on a degree in English. I spend most of my time thinking about writing, teaching, and learning, and how these three complex processes are related. Over the last four years teaching college writing classes and studying composition and rhetoric, I have learned to think about writing in complicated ways: writing–both alphabetic and digital–is at once tool for making things for others (finished texts) and also a tool I can use for myself, companion to help me become better learner, thinker, and worker. I try to teach my students to think about writing this way, and I try my best to believe it myself, to practice what I preach. I know that I am never done learning to write, and that writing about my own learning process is the best way to speed this learning along. Which leads me to question two:

What (is this blog about)?

I’m calling this a learning/doing blog. I am picturing it as a mix of an informal publication venue and a process journal for my writing and research work. To keep me working on my various article and dissertation projects, I will post drafts and chunks of writing that are parts of larger works-in-progress. Feedback and suggestions are welcome. I will also post reflective writing in which I take a step back and talk about my process as a developing academic writer–what’s working, what’s not, what’s next. At some point, I will more fully flesh out the theoretical underpinnings of this blog project–what exactly I mean by learning/doing. In lieu of a thorough explanation, I’ll give you an idea of the ground I mean to cover.

Where (will this blog go?)

You can expect posts on this blog to include things like this:

- Drafts and chunks of writing for conference talks, dissertation chapters, webtexts, videos, and other formal products

- Musings and speculations on ideas emerging from my research

- Report-backs from workshops or other public events (done by me or by others)

- Reflections on my experiments with various digital tools or writing techniques

- Coming soon: my experiments with the digital mapping/composing tool Mural.ly

- Rants and diatribes about life as a graduate student, my learning process, and Beyonce-themed podcasts

When (will I post?)

I’m planning to post at least once a week, probably by Fridays. While I would like every post to be interesting and important, the truth of the matter is that this blog is more about process than product. The important thing for me is that I post something every week: it’s about routine, not revelation. It’s about committing to a process that will help me develop healthy writing habits and keep my demons of self-doubt in check. So you can expect some variety from week to week in terms of format (and probably quality too). But I promise to update every week.

Why (should you read?)

I can imagine some reasons why you might read my blog. Perhaps you are a graduate student yourself, and you’re also struggling to develop your professional identity, your writerly voice, your teaching style, all that. Maybe you too are thinking about writing a dissertation and want to stay sane (whatever that is) while doing it. Or perhaps you share similar research interests with me, and you’ll be interested in my ideas and scholarship on disability or pedagogy or literacy. If this is the case, you might check out my annotated bibliography archive, where I review and respond to the books and articles I’m reading. Perhaps–and this feels unlikely–you simply like the way I write, or you know me personally or want to get to know me better. Maybe you simply enjoy reading what I write and it has no particular utility to you at all.

How (should you interact?)

Whatever your reasons for reading my blog, I want to encourage you to interact by commenting, contacting me, or spreading the word through social media. Whether I’m posting polished drafts or loose musings, I would love feedback: disagreements, questions, corrections, encouragements, anything. I want to start discussions. So, please, don’t be shy.

Those are the facts. Stay tuned for more soon. And thanks for reading.

CWPA 2014 Presentation

Administering Disability: Institutional Histories of Access and Accommodation

Presented 18 July 2014

By Andrew Lucchesi, CUNY Graduate Center

Please leave comments or email me at a.j.lucchesi@gmail.com with questions

Follow me @AJLucchesi

I will be presenting today about a research project I am currently undertaking to study the history of disability administration within the City University of New York system. In my project, I investigate the various kinds of labor disability service providers have done individually and collectively to shape policies, develop and allocate resources, and foster disability culture across the CUNY system over the past forty years. By taking seriously the intellectual and political lives of disability service providers, past and present, I hope to show how disability-conscious WPAs who can learn strategies for improving accessibility not only in our own programs but across the landscape of higher education.

1. Bureaucracy as a site of intellectual labor

Disability service providers (DSPs) have a bad reputation in many camps as mindless, faceless bureaucratic functionaries. This assumption, commonplace today, misrepresents the diverse and long history of disability service provision on campuses in the decades since the passage of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 which first brought compliance officers to American colleges and universities to manage disability issues. As faculty and faculty/administrators, we are aware that our campuses have an office that handles disability issues and academic accommodations; often, however, we have little idea who these people are or what their jobs actually are. Most of what we know of their labor we learn from the accommodation letters we receive, instructing us, often in a legalistic tone, how we must change in some established curricular practice: usually by offering students extended time on exams, or whatever else the DSP has deemed a “reasonable accommodation” based on the student’s undisclosed disability needs. Many faculty respond to these letters with bewilderment — how can I give extra time on exams when I use portfolios? — or see them as adversarial — you will comply because it’s the law!

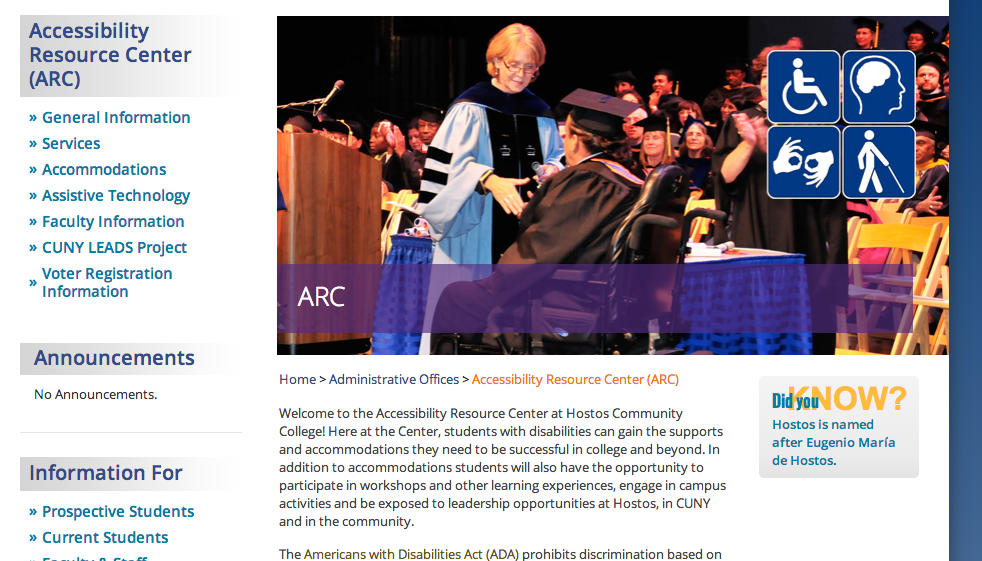

Image shows a screenshot of the webpage for the Accommodation Resource Center at Hostos Community College. Large banner shows a professor in regalia shaking hands with a graduating student using a wheelchair.

In the past, Disability studies scholars have often expressed a blatantly critical stance on the work of disability service provision. As legal-medical authorities within the broader administration of the contemporary corporate university, DSPs hold significant power over the students they work with: they get to determine if the student has provided sufficient proof of legitimate disability, and they get to decide what is a “reasonable” accommodation for the student to receive. This routine administrative requirement to provide or deny accommodations to a student can have powerful consequences, both in terms of student success and in terms of the substantial financial investment associated with some accommodations. As Tanya Tichkosky argues in her 2011 monograph on questions of access and disability in higher education, the current bureaucratic system of disability accommodation, as administered by DSPs, reinforces the commonplace notion that disability is a problem that individual disabled people need to deal with, that it’s a personal problem caused by the disabled person’s impairments (9). This mentality, Tichkosky and many others argue, leads administrators and faculty alike in the university system to believe that disability is only an issue when there are disabled people around, thus hindering them from recognizing disability as a social phenomenon produced when spaces, curricula, and cultural conventions are designed to accommodate only a limited portion of the population. We can add to this theory-based criticism the plethora of disability service horror stories told by disabled students and scholars alike who have been denied services for offensive reasons or put through undue hardship to prove their disability before receiving legally guaranteed accommodations (see, for example, this recent piece: “Why Are Huge Numbers of Disabled Students Dropping Out of College?”)

If we judge based only on the perspectives published in disability studies or the anecdotal experience of WPAs and faculty, the best image most of us get of DSPs is that they’re well-meaning bureaucratic functionaries, rubber stamps, paper pushers – perhaps at worst, they appear to be adversaries to both progressive disability activism and faculty autonomy alike.

For me, as a student of Writing Program Administration scholarship, I tend to be wary of arguments that draw us/them battle lines between administrators and faculty, regardless of the disciplinary context. WPA scholars like Richard E. Miller and Donna Strickland have argued that while faculty (especially politically progressive, activist intellectuals) tend to distance themselves from the work of done by management, the fact is that university work at all levels exists within a matrix of bureaucratic control and administratively sanctioned access.

Strickland, for example, claims that composition studies, despite the forty year history of established Writing Program Administration scholarship and professional identity, continues to repress the managerial aspects of our profession in what she terms the “managerial unconscious” of the field. We go to extreme lengths to bill ourselves as teachers and theorists, repressing the fact that it is our talent for working with and within the administrative constraints of the university system that gives us the ability to execute new programs and grow our field. Miller, in his historical study of experiments in progressive reform in higher education, argues that rather than distancing ourselves from administrative roles on political grounds, faculty and WPAs alike should learn to see ourselves as “intellectual-bureaucrats;” we should acknowledge, he argues, that the bureaucratic aspects of our labor as a source of knowledge and site of scholarship, as well as, ultimately, a mechanism for progressive change. He writes,

To pursue educational reform is thus to work in an impure space, where intractable material conditions always threaten to expose rhetorics of change as delusional or deliberately deceptive; it is also to insist that bureaucracies don’t simply impede change: they are social instruments that make change possible (Miller qtd in Strickland 12).

Here Miller describes the reality that anyone who would work for progressive change in the landscape of higher education must confront the messy, vexed reality of bureaucratic life. Disability Service Providers, like WPAs, confront every day the “intractable material conditions” of disability administration. Instead of seeing DSPs as mere bureaucratic functionaries, I suggest we seek to know them as fellow intellectual-bureaucrats; to do this, we must look to the ways they have altered the bureaucratic landscape of higher education. In what follows, I will describe a large-scale ethnographic research study I am currently undertaking to increase our knowledge about the institutional work of disability service providers across a range of campuses of a large urban university system.

2. Disability Administration in CUNY

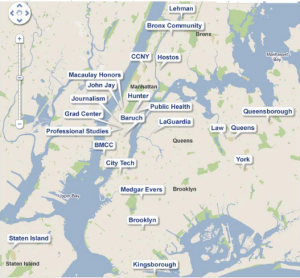

The City University of New York system (CUNY) is comprised of twenty-four institutions, including seven community colleges, eleven four-year colleges, three graduate schools, a range of cross-campus institutions, and a core managerial unit called CUNY Central Office.

Each teaching campus has its own autonomous disability services director with its own (centrally distributed) budget–all under the oversight of CUNY Central’s Assistant Dean of Student Affairs, Christopher Rosa. Those of you who are active in disability studies may recognize Rosa, who is himself a former DSP from one of the senior colleges, as a published disability scholar, prominent disability rights activist, and prominent member of the Society for Disability Studies, the organization the publishes the field’s most prominent journal (Biography,http://caaid.us/Bio3.html, accessed 16 July 2014).

As I’ve suggested, most faculty knowledge about disability administration and the DSPs who labor there is anecdotal, based on individual encounters between faculty, students, and service providers. This is true both of disability scholars and of WPA and writing scholars. Most people only know the disability service staff on their individual campus, which can lead to over-generalizations. Most critics of disability service provision speak of disability administration as if it were unchanging as well as unchangeable, a universal state of affairs. As we know from numerous studies of Writing Program Administration and assessment, administrations are always inflected by the material constraints and procedures of the local institution. Likewise, we must acknowledge that each encounter between critic and DPS is also isolated in time and removed from its broader historical context. Indeed, as my research on the administrative lives of two generations of CUNY disability service providers has already begun to reveal, the system has had a rich and dynamic history, full of change and innovation, often powered by the very activist imperatives at the heart of disability studies.

3. Methodology

My research consists of three main components. The first stage involves individual interviews with current and former DSPs from around the CUNY system. I have identified two primary populations, whom I will refer to as “old guard” and “new guard” DSPs. Old Guard began their work in the CUNY system either before the implementation of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (which wasn’t actually enforced until 1978) or they began their work as DSPs within the first decade of the legal mandate that college campuses be made accessible to people with disabilities. Because no established training or credentialing system existed for college disability administrators at the time the Old Guard started working on campuses, these individuals come from a range of professional backgrounds including clinical psychology, social work, sociology, and humanities fields. As might be expected, most of these old guard DSPs have retired and been replaced by the New Guard who inherited the administrative systems the Old Guard developed throughout the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. New Guard DSPs are more frequently professionalized for jobs in college disability administration, though certainly there still exists considerable diversity among this population.

Having identified a representative sample of Old and New guard DSPs, I am conducting individual interviews covering five main topics:

- the DSP’s professional background, including administrative training and experience with institutions of higher education;

- the DSP’s perception of disability service provision and its role on campuses (including their relationship to the broader administration or campus disability culture);

- the DSP’s approach to carrying out that role (including major causes championed, major projects undertaken, major hurdles encountered);

- the DSP’s characterization of the students receiving services through her/his office (including how student populations may have changed over time); and

- the DSP’s perspective on faculty awareness of disability issues and accommodation practices.

Following these individual interviews, I will be holding focus groups with different clusters of Old and New guard DSPs, with the aim of teasing out generational and professional differences among their perception of the DSP role.

In addition to these ethnographic components, I am also collecting a textual archive of documents produced by DSPs across the system relate to disability administration. The range of materials I am gathering includes

- publicly accessible administrative documents, like disability services websites, pamphlets, form letters, and other administrative documents;

- educational materials about disability issues, designed for students or instructors;

- non-confidential correspondence between DSPs from different campuses, or between DSPs and other branches of the administration, or between DSPs and members of the state legislature;

- scholarly writing published by DSPs based on their work on campuses; and

- curricular materials developed by DSPs for use in their student support programs.

My hope is that these written materials, which are not gathered in any established archive within the CUNY system, will provide evidence of the complex rhetorical work of disability service providers, not only as administrators of programs, but as producers of disability discourse in a way hitherto not acknowledged. (If anyone knows of a comparable archive anywhere, please let me know!)

4. Findings (so far)

I am still in the early stages of this project, conducting individual interviews and gathering my initial archival materials. At this point, I have spoken with three old guard DSPs and one New Guard, and through the course of these interviews gathered the names of other key players in the administrative history, whom I will be contacting over the next year. My aim is that by the end of Spring 2015 I will be completing my focus groups and developing my findings into both material for my dissertation and a standalone oral/textual history project.

5. Discussion

At this point I can make a few general observations based on the insights that are emerging from the research so far.

A) Council on Student Disability Issues

One important finding from my interviews so far is the central position collaboration has played in the professional lives of CUNY DSPs. Indeed, in her or his own way, each interview subject attested to the importance of CUNY’s campus-wide Council On Student Disability Issues (COSDI). COSDI, which is comprised of the directors of disability services from each of the campuses, has long served as a hub of disability discourse within the CUNY system (COSDI, http://catsweb.cuny.edu/?page_id=880, accessed 16 July 2014).

Image shows a screenshot from the CATSWEB page, explaining the organizational structure and objectives of COSDI. Page banner shows the skyline of New York.

For DSPs isolated on different campuses, COSDI meetings and shared correspondence provides a venue for sharing local issues and workshopping novel solutions to administrative problems. In the early days of disability administration, when administrative policies and best practices were still being developed, this organization served as a forum for debate, a staging ground for collaborative action, and a space for mutual support among often beleaguered professionals.

So far, I have managed to piece together portions of the organizations’ history from my interviews with the Old Guard DSPs, all of whom served as co-chairs of COSDI at some point in the past. It has become clear, however, that a more thorough investigation of this organization will be key to my research. I have not yet assessed the quantity of meeting minutes or internal documents that still exist from the first decades of the organization’s history. These may prove to be key in understanding the development of disability administration in the CUNY system.

B) Beyond Disability Management

A second key revelation of my interviews so far relates to the diverse nature of the non-managerial work performed by DSPs in the system. For now I will break this labor into three categories: political, pedagogical, scholarly.

Two Old Guard DSPs I interviewed, both with professional backgrounds in social work, reported being involved in local state politics as part of their work as DSPs and members of COSDI. One told a story of how in the early 1980s, COSDI members, who had to this point had no stable budget lines for their offices, decided to lobby the state capitol for a annual allocation of funds for disability services in CUNY. Using data meticulously gathered by COSDI members over the early years of their work, and bolstered by student activist groups that COSDI members had helped form on their home campuses, COSDI successfully lobbied Albany and secured a stable annual allocation that is still the primary source of funding for disability services to this day.

The third Old Guard DSP I spoke with shied away from the more political work of COSDI; as a trained psychologist with a background working as a school counselor both in Brooklyn elementary schools and for the New York Department of Education, he preferred to engage with the DSP role from a pedagogical and counseling perspective. This DSP, who helped establish the CUNY Learning Disabilities Project, described to me a number of pedagogical innovations he designed and implemented during his time as DSP at one of the CUNY community colleges. For instance, he developed a two-semester, credit-bearing course sequence for students in academic distress (not all of whom had documented disabilities), a course sequence that integrated into one curriculum that he co-taught a mix of introductory literacy instruction, student support, and self-advocacy coaching. He also produced faculty development materials to help instructors adapt their teaching practices to be responsive to principles of universal design, including insights from developmental psychology about multiple and multisensory learning styles.

Finally, I want to give a few examples of the scholarly work of these DSPs. COSDI members were responsible for producing a range of publications that were published within the CUNY system. For example, one Old Guard DSP whom I haven’t interviewed yet co-authored Dispelling the Myths: College Students with Learning Disabilities a comprehensive guide for instructors and administrators about relevant research on Learning Disabilities and best practices for accommodating instructional practice to accommodate their needs.

Image shows cover page of Dispelling Myths: College Students and Learning Disabilities, second edition, written by Katherine Garnette and Sandra LaPorta, 1991

I should note that in a move that sets this 1991 document ahead of most similar documents circulated even today, Dispelling the Myths incorporates student perspectives in the form of first person narratives and also addresses issues of social stigma and faculty ignorance as factors that make universities particularly disabling spaces for people with LD. This focus on the environment as the problem, rather than the disabled persons’s deficiency, is consistent with current disability studies approaches. Scholarship like this, created by intellectual-bureaucrats working just a few departments over from Hunter College’s WPAs, could serve as a valuable model for our own field, which continues to struggle in moving beyond purely medicalized views of invisible disabilities like LD.

One further example shows some of the discursive complexity evidenced by this history. Here I reproduce the abstract and first page of an essay titled “Clinician, Administrator, Education: Reconciling the Roles” by Anthony Colarossi. Colarossi, the school psychologist turned DSP I discussed earlier. This essay, which Colarossi presented as a talk at the 1988 conference of the Association on Higher Education and Disability (AHEAD), reasons through the complex institutional positioning of the DSP role. In a narrative that would ring true to many WPAs, he describes how the multiple roles DSPs serve often conflict, necessitating difficult compromises between his ethical imperatives as an educator and his professional obligations as an administrator.

Image shows first page of Anthony Colarossi’s essay “Clinician, Administrator, Educatior: Reconciling the Roles” as published in the conference proceedings of the 1988 AHEAD conference

While Colarossi describes a range of programs he developed for learning disabled students on his open-admissions campus, he concludes that it is “the manner in which services are provided is as important as the services themselves.” Here, while acknowledging the substantial administrative constraints working against DSPs performing their jobs with adaptability and sensitivity, he resolutely acknowledges the need for DSPs to deal with the social and cultural forces that produce the isolation and stigma disabled students so often experience. Again, this should sound familiar to this audience.

Again, sentiments like these should be familiar to us as WPAs: our own scholarship attests to the difficulty of swapping among the hats of our composite pedagogical/administrative roles, the struggle to remain sensitive educators while also managing ornate and expansive systems. If this published talk is representative of the kind of discourse that has been exchanged among COSDI members throughout the years, we may have much to learn from recovering this discourse.

6. Conclusions and Leads

I will conclude with the final insight from my research so far: a lead, really, a new question to test that has emerged through my conversations. All of the Old Guard DSPs reported perceiving a generational split in terms of approach to disability service provision between themselves and the New Guard. Whereas Old Guard characterize the early years of disability services as being rich with innovation, they frequently remarked that disability services had become progressively more routinized over the years. They spoke of New Guard DSPs as having inherited relatively stable administrative systems, systems that they have not continued to innovate and develop with the same activist mentality as the Old Guard had. Obviously, this kind of assessment, coming from the Old Guard, will need to be balanced by perspectives from the New Guard.The one New Guard DSP I spoke with was too new to the system to have a strong perspective on this topic.

However, this belief from the old guard offers some intriguing possibilities for my study as I cary it forward. If current disability studies scholars are correct that some (or even many) DSPs today approach their role primarily as managerial functionaries of disempowering disability administrations, perhaps it has not always been this way. Perhaps by investigating the way the role of disability service providers have changed over time–how they have morphed, expanded, diversified, or unified–we will learn something important about the work of intellectual-bureaucrats in the contemporary managed university. The tools of WPA and comp/rhet scholarship will be particularly useful in this project, especially our methodologies of archival history, ethnography, and rhetorical analysis. We may discover lessons that we as WPAs can benefit from, especially as we accept disability activism as part of our own role on college campuses. This history, I believe, will teach us something about how our colleagues across the campus and across time have learned to, in Richard Miller’s words, “[tinker] at the edges margins of the academy,” how they have worked institutional change in the only way it’s really possible from within the current system, by “discovering the possibilities that emerge when one sets out first to enumerate and then to work on and within extant constraints” (212). I am eager to report back with more as my research continues.

7. Works Cited

Colarossi, Anthony. “Clinician, Administrator, Education: Reconciling the Roles,” Published with conference proceedings from the 1988 AHEAD conference.

Garnette, Katherine and Saundra LaPorta. Dispelling the Myths: College Students with Learning Disabilities. New York: Hunter College, 1991.

Miller, Richard E. As If Learning Mattered: Reforming Higher Education. Ithica, NY: Cornell UP, 1998.

Smith, E. E., “Why are Huge Numbers of Disabled Students Dropping Out of College?” Alternet.org 20 June 2014. Accessed 17 July 2014.

Strickland, Donna. The Managerial Unconscious in the History of Composition Studies. Southern Illinois UP, 2011.

Titchjosky, Tanya. The Question of Access: Disability, Space, Meaning. University of Toronto Press, 2011.

Beat the system, win the game: Response to Mooney and Cole’s Learning Outside the Lines

In their hybrid memoir/self-help book, Learning Outside the Lines: Two Ivy League Students with Learning Disabilities and ADHD Give you the Tools for Academic Success and Educational Revolution (2000), Jonathan Mooney and David Cole reflect on their experiences as LD/ADHD students who endured educational failure and went on to succeed in the Ivy Leagues, not by conforming to the mold of traditional education, but by accepting their unique strengths as atypical learners and beating the academic game. They aim their book at other LD/ADHD students who are poised to make the leap into college; using a playfully wry tone, they deflate the hype of college as a utopian environment for learning, instead calling it what it is, a landscape that can be as restrictive and disempowering as elementary schools often are for LD/ADHD students. Learning Outside the Lines offers readers a set of models for confront the challenges of being an LD/ADHD college student realistically, showing that academic success is possible and within the grasp of even people who have faced extreme educational failure in the past.

The first section of the book is the most akin to genres of creative nonfiction. The first two chapters present biographical narratives from the two authors, documenting their traumatic experiences in elementary and high school and their eventual acceptance to Brown University where they met. In both narratives, the authors recount how they were demoralized and alienated from prescriptive educational systems sadistically bent on matters like spelling, handwriting, and sitting still. Despite the authors’ considerable creative skills as storytellers and artists, they were made to think of themselves as lazy, crazy, or bad — identities they were only able to dispel as unfair later in life. Here Mooney, who had discovered his talent for English studies, finds himself once again failing under an instructor who believes spelling and handwriting trump creative skill and inventiveness:

“I wanted to tell all of [the other students] that good handwriting and spelling and following the rules of some pathetic high school English teacher did not make them smart. But the most frightening thing that I grew to understand that year is how intelligence is a construct, and the rules of that environment, where form is the gatekeeper to content, did make them smarter than I was” (42)

Thanks to the autobiographical focus of the book, theoretical observations like Mooney’s musing on the constructed nature of intellignece emerge as reflections on lived experience, rather than theory for theory’s sake. In the chapter that closes their autobiographical segment of the book, “Institutionalized,” the authors reflect on how they met at Brown university and came to recognize their experiences as indicative of skewed institutional priorities in the educational system. In particular, they characterize most elementary education as being about moral and behavioral training, wherein students are taught that whose who learn easily and behave appropriately are rewarded and thought of as good, and those who learn poorly in the received environment and disrupt the order of the classroom are punished and treated as morally bad. While diagnosis of learning disability and ADHD in some way justifies this “bad” behavior, it does not identify the problem of the system in the environment, but instead locates it in the deficient/medicalized student.

Based on this experience, the authors lay out a curriculum for self-empowerment aimed to help their readers achieve academic and personal success. The key features of their plan are as follows:

1. Confront the trauma of educational failure, including lingering psychological effects

2. Understand individual strengths and weaknesses

3. Understand the tasks and rules of academic success in this new educational environment (colleges and universities)

4. Build skills and work habits that work with individual strengths and weaknesses

5. Build a positive self-image outside of academic performance

The majority of the book is devoted to number 4. In “Schooled,” the authors break down the necessary academic skills needed for success into chapters on topics like note taking, class participation, exams, and writing. In each one, they offer multiple routes to success, each articulate to match different learning styles. Employing Howard Gardner’s model of multiple intelligence, they allow readers to mix-and-match the study habits that will work best for them, including a heavy emphasis on oral, social, kinetic, and multisensory approaches to learning. In addition to these learning and performance tips, they also advocate self-advocacy skills, such as arguing for appropriate accommodations, and also recommend the usefulness of student support services like writing centers and campus mental health services.

I was impressed by many of the recommendations Mooney and Cole make in their extended skills section. Most compelling to me was their breakdown of the difficulties LD/ADHD students face with writing. In essence, they identify writing as a constraining linear practice, which opposed LD/ADHD ways of making/thinking which tend to be visual and multidimensional. Here’s an exemplary passage:

In short, our thoughts are three-dimensional, but the medium of writing is at best two-dimensional, drawing primarily on logical and sequential skills. . . . The second reason writing is so difficult is a historical one going back to elementary school (you could have guessed that one). Those feelings of shame and emotional distress while writing come from the fact that at an early age, we learned that writing is the gatekeeper to intelligence, right up there with reading. . . . However, writing is a confused and dishonest academic discipline.” (159)

Taking this skeptical view of academic writing, the authors break down the “game” of successful performance on a large writing task into tiny parts, offering students multiple alternatives for navigating the writing process designed to suit their individual writing processes. To make the process more manageable and less anxiety provoking, they advocate a system of multiple drafts, incorporating a range of visual outlining and brainstroming practices, peer feedback, and mental focusing activities. Their suggestions strike me as pedagogically sound, and their breakdown of the specific difficulties LD/ADHD folks face in writing will be useful for me later on in my research. I could imagine assigning this chapter to introductory writing classes at almost any level.

While I’m talking about writing, I should mention a growing trend I’m noticing in these memoirs, namely the way they reference their own composition. Looking back, Harry Sylvester, who described himself as a total non-writer, made much of the dictation/peer editing process he used to compose his memoir. Similarly, Temple Grandin describes her own compositional process changing over time as she comes to understand NT and ND people better. In his foreword, Oliver Sacks comments on the licidity of Grandin’s most recent memoir compared to her earlier work, which needed editors and co-writers to be coherent to an audience.

In Learning Outside the Lines, Mooney and Cole describe their composition process in similar terms, citing collaboration as a key factor in their success. Mooney and Cole collaborated on the book’s outline, but Mooney wrote the majority of the actual content, they explain. Cole (I gather from his narrative) has more extreme writing anxiety and less interest in literary expression (he is a visual artist). Mooney, however, explains multiple times in the book that he is entirely reliant on his mother for proof reading and copyediting, and he has a practice of faxing her manuscripts for correction, including the MS for this book.

I am not sure what to make of these moments where attention is drawn to the composition process. In one sense, they are unusual only in that the authors are drawing attention to a process that is typically erased by able-minded authors. Another author might give their editor a polite thank you in the acknowledgement, but they will typically not reveal the full negotiationan and revision process the work went through: this is all erased in the process of taking on the authority as “author” of a finished work. However, in the case of these memoirs, they are speaking to an audience of ND outsiders, who might see a project like writing a book as impossible. By foregrounding the collaborative composition process that went into making the books, these authors combat the idea that one kind of mastery alone is acceptable credential for writing a book that others can read, learn from, or even love. It’s perhaps a quality that identifies these memoirs as specifically disability memoirs.

One final point I want to mention is about the presence of institutions in this work. They focus much of their attention on the problems in elementary education and how restrictive opportunities for intellectual and creative engagement often result in trauma and disengagement from LD/ADHD students. They also comment on college environments, which they claim have the ability to be more open and accessible, but often fall into the same ruts of uniformity and oppression.

One important aspect of making education more open and effective, according to these authors, is the use of multisensory, project-based learning as opposed to uniform, standardizable means. They speak to the power of experience in the learning environment, building things, epermimenting, rather than simply relying on reading and writing to conduct learning and evaluation. They claim that there is no model in higher education that would institutionalize practices of multisensory, experienced-based learning — though I can think of a few methods that I admit have not taken on massive application, like service-based learning, digital-humanities-style making and building, blog and design projects, and the like. I imagine building a stable writing program around these kinds of experiential learning styles and building the kind of institutional environement Mooney and Coles ask for.

My final observation about institutionality is one that I noticed from other memoirs by LD educators, that is pull toward making new, alternative educational environments as the natural extension of theory based on lived experience. Mooney and Cole founded Eye to Eye, a national mentoring program that offers afterschool support to LD/ADHD children around the nation by linking them with LD/ADHD tutor/mentors at local colleges and universities. Likewise, Paul Schultz in his memoir My Dyslexia ends his narrative of self-discovery by describing how he founded an alternative creative writing school based on his insights about LD literacy talents for creative writing. This move to establish new learning spaces seems key for LD authors especially. More than simply succeeding in traditional academic environments, these authors seeks to model better environments by inventing novel systems of support and new ways to define success.

In the next few days, I will be posting some shorter blog entries on two more theoretical books I’ve been working through this week, Richard E. Miller’s As If Learning Mattered: Reforming Higher Education, and Judith Halberstam’s The Queer Art of Failure. I don’t think I’ll have that much to say about either of them, based on the notes I have, so I’ll be able to keep the posts short and to the point.

Mooney, Jonathan and David Cole. Learning Outside the Lines: Two Ivy League Students with Learning Disabilities and ADHD Give you the Tools for Academic Success and Educational Revolution. Foreword by Edward M. Hallowell, MD. New York: Fireside, 2000.

Notes: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ekjURwMejy8CW5ggwN6fALWRaA09P0Aq_38Hw8d57nQ/edit?usp=sharing

Speaking from Experience: Response to Harry Sylvester’s Legacy of the Blue Heron

It’s been another long time away, dear Reader. I’ve spent half the semester running around, giving conference talks on disability and writing studies, and this has meant sadly neglecting my orals reading and this here blog. I hope to get some video versions of those talks up and running eventually, and if I do I’ll share them here.

However, now I’m back on the righteous path, reading and writing as much as possible. I’ve resolved to take my exams in the first week or two of September, so I have until then to get through the remainder of my reading lists.

For my list with Jason, I’m spending some time with memoirs by neuro-atypical authors writing memoirs about their educational experiences, esp in relation to higher ed. For this post, I’ll discuss Harry Sylvester’s Legacy of the Blue Heron: Living with Learning Disabilities (2002). Since this is my first post back after a long break, it’s going to be particularly unfocused and fragmented, mostlikely. I’ll get back into the swing of things soon and producing more readable posts. Bare with me, please.

This slim memoir dictated by Sylvester, a former president of the Learning Disabilities Association of America, aims to show how claiming understanding and acceptance of learning disabilities can help people claim ownership of their lives and . . . . . . .

Similarly to how Temple Grandin’s memoir alternates between following her own autobiographical narrative and focusing on topics of interest for her disabled population, Sylvester’s memoir moves through his life in major themes, each life period generating a thesis of sorts. In his chapter School Days, Sylvester describes his natural aptitude with machines, engineering, mathematics, and design–he contrast these aptitudes, for which he got parental and school-based encouragement, with his extreme weaknesses in spelling, writing, and reading. Having been educated during the 30s and 40s, there was little understanding of LD at the time, and Sylvester underwent substantial disciplining to correct the presumed “attitude problems” that were keeping him from succeeding like the other kids. As he says, “I was being punished because the school didn’t have an effective reading program for me” (8).

His experience of humiliation and punishment around literacy performance continues into his college years. While succeeding at the top of his engineering classes, he is publically chastized by his English teachers who tell him he is not suited for college because of his handwriting and spelling primarily.

The upshot of his analysis of his educational experience is that school systems tend to be designed for typical learners who can process language in predictable ways, and when students do not succeed, they are often blamed for not fitting into the system. Linguistic ability must be “explicitly taught” to students with LDs, employing multi-sensory phonetics training from an early age, he believes.

Though Sylvester leaves school successful in his degree, he takes with him the shame of his literacy failures. He describes trying to hide his spelling and reading difficulties in his work life: “I was so ashamed of my literacy problem that I did everything I needed to do to keep it a secret. I didn’t want people to know how “dumb” I was. [. . .] As I look back at all of this, I can see that keeping that secret was more disabling than the disability” (27).

At the same time that he tried to distance himself from his shame about literacy, he also recognizes his unique capacities for visual perception and its usefulness in his career as an engineer. In one passage, he describes his ability to visualize the design of a boat before he ever starts building it, a capacity that allows him to test out different designs and revise his plans based on the mental projections he generates for himself (31). He says it’s better than Computer Aided Design because he can do it freely in his mind. Temple Grandin describes a similar capacity when she talks about how she “thinks in pictures,” and how she designs prototype components of her feedlot equipment before ever drawing up plans. Both of these memoirists claim this powerful visualization capacity and apply it to the field of engineering — though their disabilities are very different. The upshot here is, of course, that LD is entirely context based, and that LD individuals can find jobs well suited to their strengths and succeed.

Throughout the narrative to this point, Sylvester has not yet been diagnosed with LD. In the third chapter, he reads a narrative by another LD writer and is deeply affected when the story he reads forces him to relive his school trauma. As he learns more about LD, he starts to reach out to others who experienced school failure like he did, and he also feels motivated to get diagnosed so that he can more fully understand his disabilities. Once he is diagnosed, he spends the remainder of the chapter explaining the specific learning disabilities he has and how they affected his experience in school and life.

This leads to one of Sylvester’s central arguments in this memoir: LD people must understand and accept their impairments in order to take control of their lives. This acceptance takes some re-thinking of central myths that affect the lives of all of us educated in an ableist system. We must admit that linguistic proficiency is not a universal marker of intelligence. We must to admit that our brains work in ways that make literacy tasks more difficult for us than for other people, and that this doesn’t make us less intelligent. Until we understand the specific weaknesses of our brains, we cannot accept them as part of us and find ways to be successful.

From this moment of epiphany, Sylvester moves on to become a full-time LD professional, leading support groups and national organizations on LD. He draws together anecdotes from the many young people and adults he worked with in this capacity to draw out a few other important issues with LD, including the social and emotional costs. He notes that an enormous proportion of people incarserated and in drug addition programs have LDs or ADHD. He also notes how social pressures in schools to perform in uniform ways can drive students to act out, close off, or become isolated.

One key tool this book offers to educators and parents is a model for LD support groups. He explains how he developed a system of emotional/social support for LD people to identify and claim their difficulties while at the same time also claiming and taking pride in their strengths. Interestingly, he offers Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligence as a useful model for helping support group members start to understand their strengths and their weaknesses in context. Here’s a useful quotation (actually from the first chapter, but it pre-empts the discussion of MI theory in useful ways):

“It takes a long time to realize that there isn’t anything wrong with being learning disabled or dyslexic. It means that we have different abilities and disabilities than the norm. Some people are not musical, and it doesn’t matter; they still succeed in school and in life. Other people are not athletic, and it doesn’t matter. Unfortunately, in a society where language and math are so important, for those of us who cannot do language or math it does matter. Our differences become disabilities.” (17)

So, two key insights here: First, like Gardner, he argues that some capacities are more privileged in society than others. Indeed, the kinds of capacities we even pay attention to and value as intelligences are historically and culturally specific. Second, through the process of support group work, Sylvester aims to help others understand that being linguistically weak is not something to feel shame or self-pity about. It’s something to accept and keep in proportion to the strengths of each individual.

In the end, Sylvester offers this model of acceptance and empowerment to anyone with an LD. To educators and parents, he argues for reform and understanding. Here’s a final quotation from his conclusion:

“We as a nation have tried to educate all of our children in language and math implicitly. It simply hasn’t worked. Those who haven’t been able to learn in this way have sat in classrooms and failed. Lack of a successful education leads to failure in all aspects of our lives, such as social interaction, emotional stability, health, success in our jobs and success in relationships. All these failures lead to low self-esteem, depression, and bahavioral problems. Even people like me, who can have a career and support a family, still pay a heavy price.” (154)

Here, as he concludes, he draws together the various parts of LD identity and locates the central problem in the educational system. I am intrigued by the relationship between the identity of LD and the specific impairments presumed to cause them. For instance, one of Sylvester’s imairments (and my own) is a weakness in processing speed for visual linguistic recognition. This in and of itself is simply a way our brains work (psychology tells us), not a disability. In restrictive school environments that expect uniform performance, people like us are unable to succeed, we fail, we are set apart from other children, and we internalize messages about our lack of worth which we carry with us through life. For some who experience extreme failures, the effects can be devastating. The impairment itself is actually responsible for only the slight difference in processing ability among a range of people: the emotional, social toll is where the disability really exists.

So, implications for my own work: I am interested in what perspectives like this do to justify making/design based pedagogies in composition. I was recently at a talk about digital humanities approaches to composition and rhetoric, where one of the speakers described using CAD or circuit boards or the like in composition classrooms. He spoke of it as another kind of rhetoric, a means of communication that didn’t rely on words. I think paying attention to the unique capacities of ND learners leads us to a new understanding of the importance of non-verbal composition, including making, building, visual design, coding, etc.

I should say a few things about the writing in this book: Sylvester and his editor both explain in their preface chapters that the book is dictated because Sylvester is a “non-writer.” Much of the work describes the strategies Sylvester uses to successfully give speeches or teach classes, ways that work well with his spoken abilities. I should think more about this model as I think about the composing implications of all of these memoirs.

Quick post on OCR and PDF recognition

I’m sitting at the Wednesday workshop “Breaking Down Barriers and Enabling Access: (Dis)Ability in Writing Classrooms and Programs” and in a small roundtable we’re talking about accessibility of written materials for those who use screen readers.

One important tool is Optimized Character Recognition. When you scan a document to share with students, you can scan it with recognized text, which allows it to be read with screen readers.

There are specialty programs for disabled people that will convert scanned PDFs into OCR’d PDFs so that they can be read from a screen reader. You can also have disability services help you scan directly to OCR. However’y ou can do it yourself as well: Here’s a quick guide to OCRing a text using Adobe: http://blogs.adobe.com/acrobat/acrobat_ocr_make_your_scanned/

Tips for Ensuring OCR’d PDFs actually work:

It’s necessary to check that your OCR’d PDFs actually work! One option, as Sushil Oswal suggested is to download Microsoft’s new Windows Eyes software (for free!) and listen to the file itself.

This might not work for everyone, however. Suppose you’re Deaf or hard of hearing, how can you tell the accuracy of an OCR’d PDF?

One thing I’ve discovered from my years of scanning and listening to readings using Kurzweil 3000 is that a poorly scanned PDF will be translated to the computer as gibberish. For example, if you scan something that’s been underlined by hand, the OCR will not be able to distinguish the letters. Or, sometimes lowercase Ls are turned into 1s, etc.

A simple way to check the accuracy of your OCR scan is to try copying the text of the PDF and pasting it in another program, like MS Word. Once you’ve OCR’d a text, you should be able to highlight and copy any text that has been recognized and integrated into the file. Whatever appears when you copy the text should be exactly what the program thinks the PDF says: so if it’s full of errors, then you can expect that the student listening to the file will hear those errors. If the text copies across platforms without errors, then the audio should read without errors too. Take it from me, listening to a poorly scanned PDF is deeply frustrating.

Machines and Mentors: Response to Temple Grandin’s Thinking in Pictures

Temple Grandin is an extraordinary person by any measure. A world expert on animal science, industrial design, and engineering, Grandin has achieved a level of academic and professional success higher than any of us can reasonably hope for ourselves. She’s written both scholarly papers and popular books, and her designs for the livestock industry are used around the world. In Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism, Grandin explores how her her unique way of thinking and being in the world have helped her to understand her own successes and challenges in life.

As I read chapter after chapter of Grandin’s, Thinking in Pictures, I found myself encountering a narrative style that was unique to me. Though it’s subtitled “my life with autism,” Grandin’s own personal narrative frequently falls out of focus for long periods of the book. Indeed, rather than focusing on her personal narrative as the central structuring feature, as many memoirists would, Grandin focuses the chapters on aspects of autistic life and experience more generally. It often feels much more like a book about autism, with her own life offered as one rich example of an autistic. So each chapter contains one part Grandin’s life story, one part literature review from clinical autism research, and one part storytelling from her knowledge of autism memoirs and her personal interactions on national tours talking about autism.

One challenge of this approach is that she does not always telegraph her transition between these components very clearly–as a result, within a single paragraph she might discuss her own childhood autism symptoms, clinical studies on verbal development, and advice for teachers, all without any clear transition. The effect of each chapter is cumulative, drawing together various strands to represent an aspect of autistic life as an impressionistic whole. Because autism is so many things, and because knowledge about it comes from so many different sources, this panoramic view substitutes for declarative statements about what autism is or is universally like. The effect in the memoir is mesmerizing, and it encourages me as a reader to be pliable and to follow Grandin’s lead to more fully understand different ways of being in the world.

Thinking back to my discussion of G Thomas Couser’s work on disability memoirs, I have been trying to decide where Grandin’s memoir would fit in terms of the rhetoric of disability. What is Grandin trying to achieve in this work? Is it politically efficacious for disabled people?

It seems to me that much of Grandin’s work is aimed at helping neurotypical (NT) people understand autism in all its complexity–seeing the beauty and possibilities of autistic experience as well as the realistic challenges. She does not sugar-coat the hard parts about being autistic in a NT world. (The opposing term to NT is neurodiverse or ND.) But I am left with the feeling that the main aim of this book is to encourage NT people to embrace autistic ways of being as valuable. In this regard, Grandin must dispel prejudices against autistic people as hopeless, pitiable, and deficient. Instead, she offers ways for NT people to imagine autistic people as employable contributers to society, if only they would be adequately taught, supported, and respected for who they are (rather than rejected for who they are not).

In her chapter “The Ways of the World: Developing Autistic Talent” Grandin talks about the unique challenges people on the spectrum face in achieving academic and professional success. Again, this chapter does many things at once. It’s one of the most straightforwardly autobiographical chapters, following Grandin’s education and professional development from her when she entered formal education in a preK program for the hearing impaired and brain damaged to her present day, working as an academic, public lecturer, and freelance consultant for the livestock industry. Using evidence from her own experience, she argues for the importance of personal mentorship for autistic people, especially from those who are willing to try to understand autistic difference, rather than simply normalize it. For instance, Grandin’s high school science teacher did not discourage her fixation on cattle behavior; instead, he encouraged her to dive deeper into this obsession, to become an expert, and to pursue higher education as a way to learn even more about the topic. At the same time, this mentor helped her navigate the difficult social landscape of NT high school life: Mr Carlock’s science lab was a refuge from a world I did not understand” (107).

Grandin extrapolated this experience to talk more broadly about how autistic talent can be encouraged at school. One general principle is that fixations (a typical feature of ASD diagnosis) should not be treated as a problem to be corrected; instead mentors and teachers should try to find ways to help autists pursue their fixations in productive ways. For instance, if someone is fixated on boats, Granding thinks teachers should use the fixation to get the student interested in math, physics, design, and engineering principles. She also sees the rise of computer and internet-related fixations as a potential boon for autistic people, since jobs in the tech sector tend to accept people on the spectrum more readily than other industries, and programming skills are highly valued at the moment.

At the same time that Grandin finds rewarding intellectual pursuits to motivate her involvement in the academic and professional worlds, she also finds mentors willing to help her navigate social challenges she faces because of her autism. As she explains when discussing the rules of behavior at her rural liberal arts college, she had to learn social behaviors through explicit heuristics, making rules about what could and could not be done in a college environment. (She calls the arbitrary taboo rules “sins of the system,” for instance the high stakes rules against having sex or smoking in the dorms.)

Indeed, this is the second part of the importance of mentorship for Grandin: at the same time as good mentors are able to recognize and foster talent in autistic people, they also need to provide direct social instruction to help them understand how to interact with NT people. For Grandin, what’s important is understanding that as an autistic person who thinks in pictures rather than in verbal language, she literally thinks differently from those around her. That knowledge allows her (and other autistic people she advises) to be more cognizant of their differences and to anticipate how NT people will perceive them. Again, citing her own experience, Grandin attests to the importance of mentors who help her to understand appropriate personal demeanor, grooming, speech in school and workplace settings. If autistic people had better access to this kind of responsive and thorough mentorship, she argues, they would be more able to succeed professionally, as she has.

While she names the real challenges autistic people face in succeeding in the professional world, she also sees autism as a source of power:

In some ways, I credit my autism for enabling me to understand cattle. After all, if I hadn’t used the squeeze chute on myself, I might not have wondered how it affected cattle. I have been lucky, because my understanding of animals and visual thinking led me to a satisfying career in which my autistic traits don’t impede my progress. But at numerous meetings around the country I have talked to many adults with autism who have advanced university degrees but no jobs. They thrive in the structured world of school, but they are unable to find work. Problems often occur at the outset. Often during interviews, people are turned off by our direct manner, odd speech patterns, and funny mannerisms. (111)

This passage has interesting implications for my thinking about access for ND people in higher education, and it also has compelling activist overtones on the most practical level. She claims that for some people on the spectrum, the regimented social conventions of academic life provide a level of stability that is useful. However, interviews and other Kairotic exchanges (I’ll talk about this more soon when I write about Margaret Price’s book about mental disability and academic life) put ND people at a disadvantage, exposing them to impediments based on NT prejudice. Rather than focusing on autistic deficiency, however, she aims her message at her NT audience:

Employers who hire people with autism must be aware of their limitations. Autistic workers can be very focused on their jobs, and an employer who creates the right environment will often get superior performence from them. But they must be protected from social situations they are unable to handle. (114)

I want to think more about Grandin’s take on activism in this book. She herself is a highly verbal, emenently successful autistic person; and yet she speaks with great certaintly about the limitations of people on the more severe end of the spectrum, as she does in this passage. Another moment at the end of that chapter confronts this issue directly. Talking about the ND movement, she acknowledges that drives to “cure” autism would remove from the human population important forms of creativity and genius. However, she also says “In an ideal world the scientist should find a method to prevent the most severe forms of autism but allow the milder forms to survive.” (122) This is not a stance that sits well with my perspective of disability activism or what I’ve learned from disability studies. It seems like Grandin’s activism might be limited only to the most capable people on the spectrum; that since her message is aimed at NT employers, educators, and parents, she does not have an answer for how to imagine life for severely disabled people in the workforce or in schools. I’m not sure where this observation will take me, but I don’t think I can leave severely impaired people out of my thinking. A thread to chase later.

Accessible Stories: Response to G. Thomas Couser’s Signifying Bodies: Disability in Contemporary Life Writing (2010)

G Thomas Couser’s Signifying Bodies: Disability in Contemporary Life Writing documents the rise of disability life writing as a popular genre over the last thirty years. Whereas in the past the memoir market was dominated by celebrities, particular movie stars, athletes, and politicians, the last three decades or so have seen the proliferation of the disability memoir, which Couser names the “autosomatography” (11). Often written by people who have no previous claim to fame, disability memoirs present the reading public with stories about the experience of life with anomalous bodies (nobodies writing about bodies, he terms “nobody / some body memoir” [3]). These works force readers to “face the body” (5), to confront illness and disability not through cultural myth alone but also through the lived experience of those writing from the other side of culture’s heavily policed border between able and disabled.

Couser claims that all disability memoir provides a potential good because it offers “mediated access to lives that would otherwise seem opaque and exotic” to mainstream audiences. However, he is also careful to distinguish between disability memoirs he sees as politically empowering and those he sees as reifying of negative stereotypes about disabled life.

He draws connections between the rise of disability memoirs and the rise of disability rights activism across American culture. He claims that memoir has historically served an important political function across a range of civil rights movements. Analogies here are easy to come by: feminism, black civil rights, and gay pride movements have all embraced life writing as a genre in order to fight dominant cultural stereotypes that justify oppression. Utilizing the politics of the personal, memoir allows individuals to counter stigmatizing stereotypes and represent their lives as they themselves experience them, reframing the terms for what it means to be black or a woman or a person with AIDS, for instance. Life writing, as a popular genre, doesn’t tend to require the same kinds of literary conventions that novels or poetry rely on, and as a result, unlettered people with important stories to tell have had access to a reading public that would normally be accessible only to those with advanced literary training.

In these respects, disability memoir has a potential to serve a counter-hegemonic function within broader culture: the genre creates a counter-discourse, by enabling disabled people to represent their own lived experience to argue back against stereotyped myths about disability and the overall cultural imperative to deny disabled people live complex, interesting lives.

On the other hand, Couser admits that many (it seems, most) disability memoirs do not live up to this counter-hegemonic potential. In his third chapter, “Rhetoric and Self-Representation in Disability Memoir,” he presents a taxonomy of different rhetorical stances toward disability that characterize most memoirs. He charts a range of popular memoirs–stories of supercrips overcoming the limitations of their impairments and leading “normal lives”; stories of blind or crippled authors mourning and accepting their tragic impairments; nostalgic stories about pre-impairment days now gone; stories of impaired people seeking cures or enduring horrific treatments. Most of these narratives focus exclusively on the experience of impairment (the individual experience of loss or injury), rather than disability (the social/cultural experience of discrimination and inaccess). They employ rhetorics of horror, pity, inspiration, and in each case cast disability as a personal problem to be overcome by those strong enough to endure.

Opposed to these conventional images of disability as tragic or inspiring impairment, Couser offers on two categories of anti-hegemonic narratives: on the one hand, he discusses “emancipatory” accounts of disabled lives that focus on the disabled person as oppressed by medical authority and institutionalization (for example I Raise My Eyes to Say Yes, about a woman who was imprisoned in a mental institution under wrongful diagnosis); narratives like these function similar to slave narratives, Couser claims, drawing attention to unjust systems of oppression that control people’s lives.

On the other hand, he offers a range of “disability studies memoirs,” such as Simi Linton’s My Body Politic and Steven Kuusisto’s Planet of the Blind (which I’ve read before but clearly need to add to my lists for its discussion of his college years). These memoirs are distinct in that they do not focus on the lived experience of impairment exclusively, but instead investigate the social and cultural experience of disability. They examine the effects of stigma and stereotype, often by documenting the author’s own development of a politically engaged and affirming disability identity. In this way, they bare resemblance to coming-out narratives, wherein the disabled person stops hiding her disability, rejects negative beliefs about herself, and comes to accept her disability as an important and potentially emancipating aspect of herself. These memoirs tend to acknowledge the influence of civil rights legislation on the lives of disabled people as well, connecting the personal quite explicitly to the political.

As I was reading Couser’s book, I often stopped to think about the implications of disability memoir for people with Learning Disabilities. While Couser’s main focus seems to be on disabilities written on the body–illnesses, mobility or sensory impairments, stories that make us “face the body”–he seems also to suggest that disability memoirs about invisible, mental disabilities serve important functions too. Certainly LD memoirs like Mooney’s The Short Bus take a disability studies perspective to tell stories about slow learners that fight misconceptions, and it certainly offers political context for understanding cognitively embodied differences. But there’s something unique that’s likely happening in terms of the politics of education that LD memoirs can tell us, which wouldn’t be the focus of most other kinds of disability memoirs.

Here’s an interesting passage from a comp/rhet perspective, and one that potentially has unique implications for LD:

Writing a life is an aspect of accessibility that may seem secondary, but it is pertinent here because it is peculiar to disability: despite important recent developments in assistive technology (such as voice-recognition software), the process of composition itself may be complicated by some impairments. People who are blind, Deaf, paralyzed, or cognitively impaired are disadvantaged with regard to the conventional technologies of writing, which take for grated visual acuity, literacy in English as a first language, manual dexterity, and unimpaired intellect and memory. For people with may impairments, the process of drafting and revising a long narrative may seem dauntingly arduous. (32)

Here Couser suggests that the genre of long-form memoir writing offers particular challenges to many people with disabilities. I wonder about the possibilities for other modes of life writing that employ nontraditional literacy practices, like web publishing, multimodal composing, and collaborative storytelling. This may be somewhere my own pedagogical experiments explore. I wonder, too, about the unique challenges LD memoirists face in performing literacy in this way, and how a meta-cognitive awareness of the self as an LD or dyslexic author might influence the genre. Couser’s models for disability memoir offer some useful framing for the political and rhetorical possibilities of disability memoir, but I will have to do some considerable work on my own to figure out the unique valencies of academic disability memoir. That’s my work this semester, I think.

Next up: Temple Grandin’s Thinking in Pictures; Mike Rose’s articles on cognition, basic writing, and academic discrimination; and Howard Gardner’s theories of Multiple Intelligence.

Images of Attack: Response to David B.’s Epileptic

I’ve spent the last couple of months reading from my lists with Joe (on disability studies) and Mark (on writing program administration). I’m now starting to dive fully into Jason’s list, which explores cognitive impairments, literacy, and academic life from a range of perspectives including educational theory, neuroscience, and memoir. It’s my most challenging list, partially because it takes in so much and tries to define a topic that doesn’t yet exist: academic disability. I won’t talk much about that here, but I want to reflect briefly on what the next few posts will explore–to set my sights and size up my target.

One strand I have already read but not yet blogged about comes from composition/rhetoric researchers working in the 1970s and 80s with cognitive models of writing. Here I have Mike Rose’s articles about writers block, cognitive reductionism, and language of exclusion. I also looked at Flower and Hayes’ article version of the cognitive model of composing, which I will eventually follow up with one of their book-length studies. These compositionists don’t think much about learning disabilities, but they do employ clinical models of the mind in the course of wrestling with academic challenges — an approach closely aligned to disability in ways I will discuss in future posts.

I have also been working through some works from the Learning Disability field, both from psychology and neuroscience. These include Maryanne Wolf’s Proust and the Squid and an excellent book of bibliographic essays Learning about Learning Disabilities which has important chapters about writing and college-level success for LD people. I’ll be posting about these texts soon.

Finally, I have begun working through the memoirs. The idea here is to find accounts of the lives of disabled people’s encounters with literacy and academic life. I am covering a wide range of cognitive or psychological disabilities, but my focus is on LD as much as possible, since very little work has been done on this condition (compared with, say, autism). To help me think more critically about disability memoir, I am using Tom Couser’s Signifying Bodies: Disability in Contemporary Life Writing (2010). I have about six or seven LD memoirs I’ll be getting to and a handful of ones on other conditions that have something to tell me about literacy or academic life for folks with cognitive disabilities. Right now, for instance, I’m reading Temple Grandin’s Thinking in Pictures, which I’ll try to post about before the end of the month.

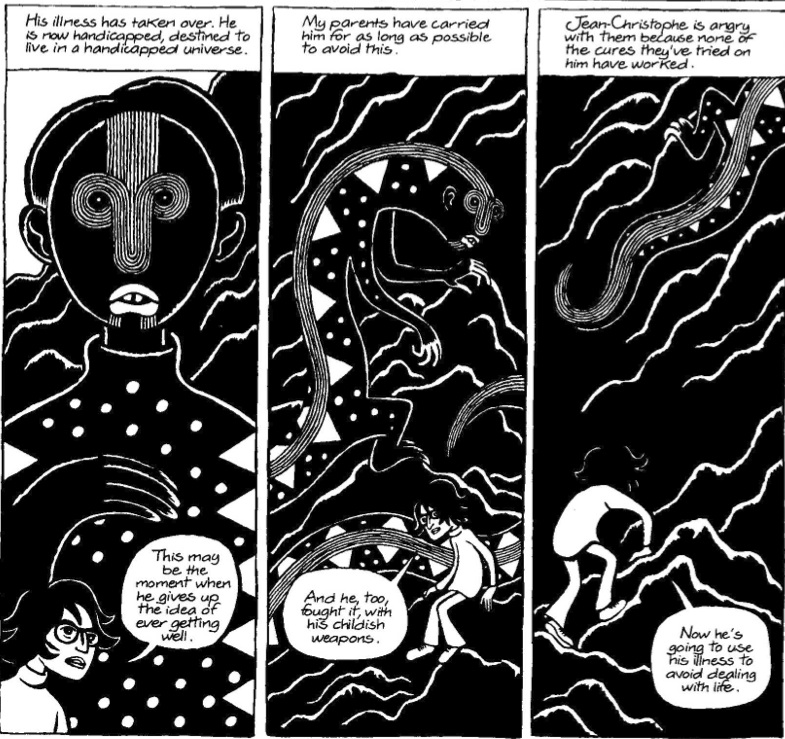

David B.’ graphic memoir Epileptic (2006) does not focus exclusively on literacy or school life. Told in the first person by David B., a well-known French cartoonist, the memoir tells the story of Jean-Christophe, B.’s older brother whose severe epilepsy comes to consume his life. The narrative tracks the family history from Jean-Christophe’s first seizure as a child through into adulthood. Epileptic documents the family’s attempts to cure or manage his condition using western medicine, macrobiotics, faith healing, mysticism, and institutional care. Rather than simply being about Jean-Christophe’s experience of epilepsy, Epileptic shows how the entire family is affected by his condition, including how they all work together to resist social stigma of the illness.

I should note here about the style of the memoir. Drawn in black and white, the style alternates between realistic representation and highly stylized symbolic imagery. One central visual metaphor: Jean -Christophe’s epilepsy is depicted as a long, spotted dragon that creeps around him, attacking him unexpectedly.

Through rapid shifts in scale and degree of realism, the memoir achieves multiple tones of voice — here’s an extended example.

Here, in the first two rows of panels, B. uses a concretely representational style to depict a conversation between himself and his mother in the 1990s. They are discussing the memoir itself which he is in the process of writing (there are a few meta-moments like this, which always catch my interest). B. has been telling stories about his grandparents, about their lives and the personal demons they faced. Here B’s mother objects to the way he’s been telling the family history, warning him that he’ll lose his readers by focusing so much on tragedies that don’t seem to have anything to do with his brother’s epilepsy. Rather than spilling the family tragedy of her grandmother’s alcoholism, she urges him to represent it abstractly, as a monster — the monster appears as a humanoid black dragon, similar to Jean-Christophe’s epileptic monster, swelling up to consume the entire frame. Returning to the family histories, the monster of alcoholism has become the ground on which the figures walk.

In the course of these two pages, we see the kind of stylistic leaps that make Epileptic spellbinding. The first two lines take a documentary tone, simply reporting realistically: real people in normal proportion, real furniture, it could be a snapshot of their actual home. This realism gives way to the fantastical, however, as the emotional weight of illness, shame, and despair creep in, until we’ve fully entered the realm of the unreal. The final frame shows B. using his storytelling voice, where we see these characters in tableau, like a picture book–not documentary, but instead representational, as in “here’s the way I imagine it”.

The central narrative follows the development of Jean-Christophe and David from childhood to adulthood throughout the 60s and 70s. We see David B’s development as an artist as he makes his first drawings and comics, as he attends art school, and as he publishes his first works. Parallel to this, we see Jean-Christophe’s initial interests in art and writing, though his development becomes stunted as his seizures get him kicked out of schools and moved into a less ambitious track of life. Soon after he is kicked out of a mainstream high school — because his seizures are too disruptive to the teachers and other students — he begins to attend a residential school for disabled youth. In one of his highly symbolic reveries, B.identifies this moment when his brother leaves mainstream schools and enters institutional care as a turning point: