It’s time again for me to post my talk from the annual Conference on College Composition and Communication (#4Cs17). This time I have for you a captioned video I made using a live recording of my talk. I didn’t read from a script, so there are a few flubs throughout. This is very much a work in progress, so I hope you don’t mind some rough edges. Feedback is always welcome.

Disability Writes

Fieldnotes on Writing, Teaching, and Embodiment

Category Archives: current projects

Experiments in Disabling the Basic Writing Classroom (DRAFT)

This talk was presented at the Council of Basic Writing Pre-Conference Workshop, The Conference on College Composition and Communication, Houston, TX, 6 April 2016.

Introduction

In this presentation, I will lay out a provisional plan I am developing for integrating disability studies principles into the daily practice of a small basic writing program at Western Washington University, a mid-sized state university in northwestern Washington State. Taking to heart the fact that this is a workshop session, I have brought you today a true work in progress. I hope you will be able to give me feedback, and that my experiments will motivate you to try some of the techniques I will discuss today.

The central question I’m trying to explore here is how can a disability-studies approach motivate me to develop novel practices in my basic writing classrooms. When I say disability-studies approach, I am referring to a philosophy that moves beyond the idea that disability is a problem to be solved; rather, disability studies honors and affirms disabled peoples’ unique perspectives and capacities. In this context, disability experience is seen as a source of insight, and disability identity is recognized as a vital cultural identity centered on values of radical acceptance of difference, mutual support, and collective action.

For the purposes of my presentation today, I am focusing on two types of disability with which I have personal experience—learning disabilities and psychosocial disabilities. For at least three decades, Basic Writing instructors have recognized the need to better understand the unique needs of students with learning disabilities, including dyslexia and other language-processing differences. In large part, our concern with these students has grown apace with the rapid expansion in the student population itself, especially at two-year colleges. In the last decade, we have also seen increased attention being paid to the growing population of students with a wide range of psychosocial disabilities. Here I borrow Margaret Price’s term to indicate a wide range of disabilities that include psychiatric conditions, emotional impairments, and developmental conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorders and ADHD (Price 2013).

I don’t want to focus today on the difficulties these students face in current-traditional basic writing instruction. There is plenty to say on this topic, and for those interested in it, I’d recommend especially Patricia Dunn’s book Learning Re-Abled: The Learning Disability Controversy in Composition Studies and Margaret Price’s Mad At School: Rhetorics of Metal Disability and Academic Life. (Incidentally, session A.01 on Thursday is focused on a the legacy of Dunn’s book twenty years after its publication.) You should also check out the excellent annotated bibliography maintained on disabilityrhetoric.com, which includes a range of articles addressing specific impairments and particular issues in traditional writing instruction.

Instead, I am trying to imagine ways that we can design basic writing curriculum that put the skills and sensitivities of people with learning disabilities and psychosocial disabilities right at the center of day-to-day practice. To illustrate what I mean, I will talk you through my plans for next fall, when I will take over as lead instructor of the small basic writing program at Western Washington University. I will describe some pedagogical experiments I am planning to build into my courses, and give some indication of how I hope to study the effectiveness of these experiments.

Basic Writing at Western Washington

Western Washington has a small, low-pressure basic writing program, especially compared to the kinds of programs in place at my graduate institution where I trained, the City University of New York (CUNY). Western has an average student body of fifteen thousand undergraduate students, with an incoming class of about 3,000 every year. These students are required to take and pass a first year writing course in order to satisfy their general education requirements. Students who enter the university with low scores on the SAT writing exam or in their high school English courses are flagged during registration for placement in the basic writing course, English 90. This course is voluntary—so students are able to opt in to the course if they feel they’d benefit from the extra writing instruction. It is graded on a pass/fail basis, and earns students three credits toward graduation.

The population served in these BW classes tend to be either first generation college students, who are usually white, or international students. It is structured as an intensive, immersive introduction to both writing and college life generally, with classes every day, Monday through Friday, and class sizes capped at 20 students.

To me, this basic writing setup offers interesting possibilities for experimentation. Students opt in, and there is no high-stakes exam structure to prepare for, which allows us room to focus on writing process and gradual development. Additionally, I see useful opportunities to link tailor the course to Western’s rapidly growing population of students with disabilities. In the past fifteen years, the number of students registered with the disability services office has grown from approximately 250 to over 1000 campus-wide. The vast majority of these students, according to the current program director, either have learning disabilities or psychosocial disabilities, or both. I hope that by tailoring the course curriculum to the needs and talents of these populations, I will be able to grow the impact of the basic writing program, and also promote more accessible pedagogy upward throughout the writing program.

I will briefly describe some curricular experiments I am planning to implement, and then conclude with some considerations about the logistics of this pedagogical research.

Learning Disability and Writing About Writing Processes

The typical impairment model for learning disability (LD) defines in terms of diminished capacities compared to the typical learner. The generally accepted model characterizes LD as a cluster of neurologically based information-processing difficulties—for example, slowness in the ability to process visual information, diminished working memory, or other weaknesses in the individual cognitive capacities required to do the work of learning. Obviously, many of these skills are important to success in a heavily reading-and-writing based college class.

Counter to this impairment model, we can also describe LD in terms of benefit or increased capacity. LD literature is full of references to increased abilities in oral/auditory information processing. Many people with LD are attentive listeners and can process audio texts without difficulty. Likewise people with LD are often confident talkers, able to articulate complex ideas without the need for written notes. Indeed, LD has historically been diagnosed by identifying extreme discrepancy between strong oral processing and weak processing of written texts.

LD is also often associated with strengths in abstract visual thinking. Patricia Dunn explored some compelling approaches to incorporating visual thinking into the writing classroom in her book Talking, Sketching, Moving: Multiple Literacies in the Teaching of Writing, for example, having students draw pictures of thesis statements or to express complex ideas in diagrams. As she points out, there is a rich tradition of visual conceptual thinking well honored in the sciences especially. Our field’s narrow focus on linear textual production—on sentences and cohesive paragraphs as the vessels of meaning—overlooks the fact that many students, can best express and understand their ideas when composing in non-linear forms.

Based on these positive understandings, and my own experiences as an LD composer, I am planning to pilot two kind of pedagogical experiments in what I’m calling dyslexic styles of composing. I’ll reiterate, these are not teaching methods designed only for dyslexic and LD students: they are mainstream practices inspired by the typical strengths of this neurodivergent minority.

First, I plan to integrate oral and audio technologies fully into my practice. The most straightforward approach I’m taking is providing downloadable audio files for every piece of class-assigned reading. To do this, I have secured through my new department a professional license of Kurzweil 3000, which is a sophisticated literacy support program designed for students and professionals with LDs. Within a single program, it allows me to scan printed texts, perform optical text recognition, and synthesize mp3 files using a range of natural-sounding voices at a range of speeds, which I can then upload to our class website. I will also include in the syllabus a number of text-to-speech generators that students can install on their web-browsers and mobile devises, which will allow them audio access to our course websites and discussion forum.

My goal here is to offer audio processing as a mainstream option for the entire class, to normalize this typically dyslexic-only practice. I also plan to take advantage of the intensive, five-day class schedule to help students explore dyslexic modes of composing.

At this point, oral dictation software is cheaply available. Indeed, it is built in to most smart phones at no additional cost. Even the gold standard program, Dragon Naturally Speaking, which used to run in the hundreds of dollars, can now be purchased for a reasonable price. These tools allow students to compose written texts using their voices, an approach that offers important benefits to all of us who process our best ideas aloud.

It is time that we more fully explore what these programs can do to help students broaden and personalize their composing processes. I think the same is true of visual mapping tools, including the ubiquitous mind mapping apps like MindMeister. Again, these tools are typically cheap or free, and they offer all students alternative means for generating ideas, growing their texts, and sharing their thoughts with others.

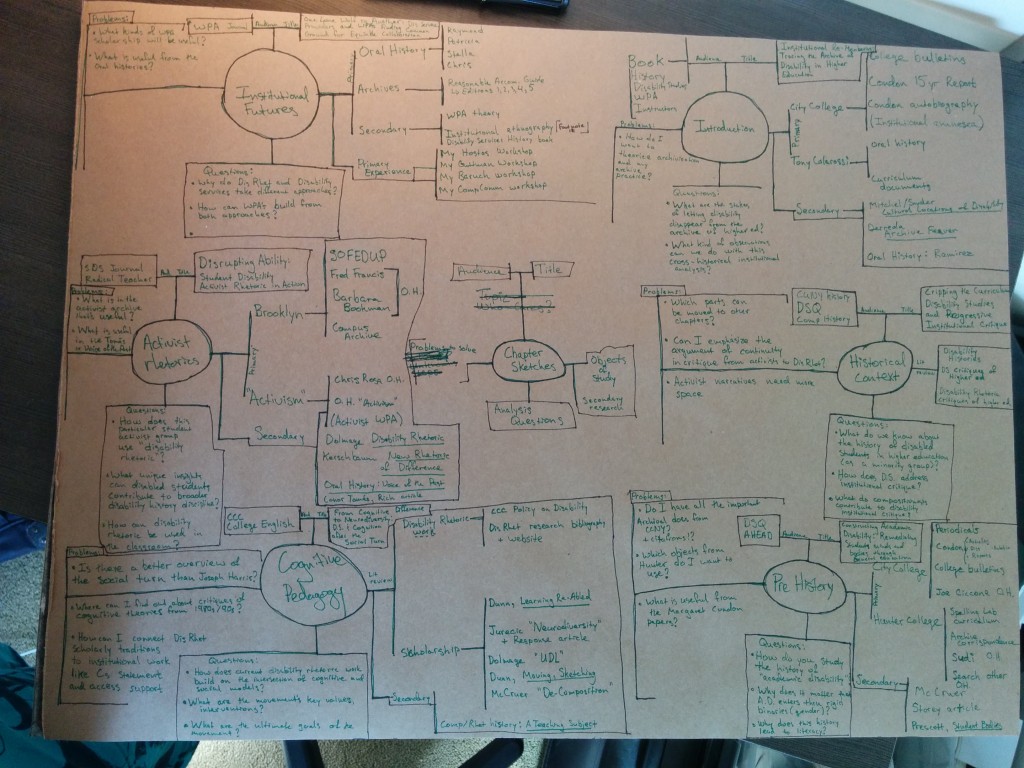

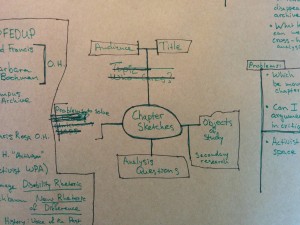

I’ll wrap up with some provocative examples from my own dyslexic composing process. While I have been teaching students to use mind mapping as a revision tool for some years, I am now working on developing formal exercises that can be used with full classrooms of students. Here, for instance, is a mind map I developed to process through the network of secondary sources in each of my dissertation chapters.

Image shows a hand-written mind map. There are six clusters of circles, each with the name of a chapter in the center. A complex web of citation, questions, and bullet points are attached to each chapter node.

Image shows the key of the mind map. A small circle extends in four spokes. At the top spoke is Title and Audience. Right spoke is object of study and secondary research. Bottom spoke is Analysis questions. Left spoke is Problems to solve.

In the center of the map is a key, which explains the meaning of each section of this node-based map.

I am developing a set of protocols that can guide students through creating such a map, similar in structure to Sondra Perl’s Guidelines for Composing. I hope that by refining this practice with some roomfuls of my basic writing students, especially within broader discussions of diverse writing processes, I will be able to develop a teachable method for incorporating sophisticated abstract visual composing into the mainstream writing curriculum.

Nagging Questions and Next Steps

I have focused here on learning disability and dyslexic modes of composition. However, I also see strong possibilities for incorporating the needs and talents of people with psychosocial disabilities into the curriculum. I’d be happy to talk about this more in the discussion, but I think particularly an attention to collaborative community building in the classroom and a deep focus on the emotional side of writing can help improve writing classes for a wide range of marginalized students.

My goals in these experiments are two-fold. For my work at Western, I hope that I can expand the scope of Basic Writing for the campus, turning it from a small auxiliary program into a vital site of experimentation. I hope as well that these courses can be a site for campus community building, where the growing population of incoming students with disabilities can learn to be academic leaders, and can see a home for themselves in the growing writing program.

Obviously, I also hope that the findings from my experiments will be useful to the field as a whole. I know that it’s hard to picture what a small, low-stakes program like the one I’ll be taking over can offer to institutions with heavy structures of mandatory remediation, ballooning class sizes, and the other difficulties that still characterize basic writing across the nation. I don’t pretend that what I do in my classroom will be universally applicable to others. However, I do think that the relatively sheltered environment of Western’s basic writing program will allow me the room to try out disability-inspired modes of teaching and writing, and thereby develop some novel approaches to accessible instruction methods. I hope you will help me think through this plan further.

Works Cited

Dunn, Patricia A. Learning Re-Abled: The Learning Disability Controversy and Composition Studies. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers, 1995. Print

—–. Talking, Sketching, Moving: Multiple Literacies in the Teaching of Writing. 2001. Print.

Price, Margaret. “Defining Mental Disability” The Disability Studies Reader, 4th Edition. Ed. Lennard J Davis. New York: Routledge, 2013: 292-299.

—–. Mad At School: Rhetorics of Mental Disability and Academic Life. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011.

Constructing Academic Disability (Draft)

This is a draft of a lecture I will be giving at Western Washington University on February 12th, 2016. It is a work in progress, and I am open to your feedback.

Constructing Academic Disability: Student Support, Social Hygiene, and the Prehistory of Remediation in New York City Public Colleges

Please explore my Prezi. A full video version of the talk is in production at the moment. For a working version, please email me at a.j.lucchesi@gmail.com

You must provide a Prezi ID for the embedded presentation to work.

Workshop: Universal Design for the Writing Classroom

I designed this workshop for the CUNY Graduate Center’s English program orientation for new teachers, held on August 25th, 2015. It was designed to give a 50-minute introduction to the principles of Universal Design for Learning and to help first-time teachers think about how they apply to their writing-intensive humanities courses. Please feel free to use it and adapt it as you see fit. And, of course, comments are welcome either in the box below or by email.

Part 1: Confronting our beliefs about ability, inclusion, and access

I want to start our conversation today with some guiding questions.

- What do we expect our students to know when they arrive in our classrooms?

- What do we expect them to be able to do? Do we imagine “baseline abilities”?

- What aspects of our courses do we expect them to find challenging?

- What aspects of our courses do we expect them to find impossible?

Prompt: Freewrite for five minutes in response to the following question. Andrew will keep track of time, just follow the ideas wherever they take you, even if it takes you off topic:

What do you believe about these things that students find challenging or impossible? When do we recognize a shift between challenging students and shutting them out?

Part 2: Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design (UD) describes an inclusive design movement originated in fields of architecture and consumer product design. The idea is that when most people sit down to design a building or an object, they start by imagining a typical user, often a user very similar to the person doing the designing.

Think about airplane seats. The designers of most airplane seats, throughout the history of that technology, have put strict constraints on the shape and size of their designs. We can look at the seat and imagine, with some surety, who the designers envisioned as their end user–what abilities and personal needs they would be expected to have.

The UD movement approaches design anticipating, at the onset, the widest possible range of users. This requires designers to anticipate what aspects of their design might impose barriers for full participation.

Notice the design elements included in this Oslo train station. What choices were made to invite a wide range of users? (Taken from the website for Zero Project, a UD initiative in Norway)

While so far I’ve been talking about UD as an architecture and design movement, UD has become a motivating imperative in the areas of web design, information design, and, of course, classroom design. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) describes an approach to classroom and pedagogical design that attempts to anticipate and invite the widest possible range of students into full and equal participation.

The UDL approach boils down to three main principles (all of which are covered in great detail, and for a range of educational settings, by the National Center for UDL):

- Multiple means of representation, to give learners various ways of acquiring information and knowledge,

- Multiple means of expression, to provide learners alternatives for demonstrating what they know,

- Multiple means of engagement, to tap into learners’ interests, offer appropriate challenges, and increase motivation. (Dolmage 2015)

The goals of these three principles are to create classrooms and pedagogies that work equitably for all students. In a moment, we’ll think more closely about how these principles apply to our work as writing or humanities teachers.

Part 3: UDL in the Writing and Humanities Classroom

Think about these components of your class:

1. How do you communicate with your students?

- What kinds of texts are they required to read?

- What kind of multi-media texts are they required to read?

- How, other than “reading,” can students learn important ideas from the class?

2. How do you expect students to demonstrate what they know?

- What kinds of assignments are students doing for a grade?

- How are you evaluating their success on these assignments?

- What alternatives are you offering in terms of using other media or literacies?

- How are students expected to understand the criteria for evaluating the success of their products?

3. How do you allow for multiple kinds of engagement?

- What avenues of “participation” are open to students who are shy, asocial, or uncomfortable in class?

- What options do you give students to choose their work based on their interest and abilities?

- What opportunities do you give students to tell you how they learn best?

In the time that remains, I want to get us brainstorming and problem solving together. Take the notecard I provided and write on it a question that you want answered about UDL and how it might apply to your work in the classroom this semester. Once you have written your question, you will work in small groups to crowdsource answers and compare your concerns with others. The most pressing questions will come back to the full group for a final wrap-up Q&A

Prompt: What do you want to know more about from this discussion of UDL and teaching? Do you want concrete examples of one kind or another? Do you want to pose a scenario or problem for us to talk through? What do you need before you walk out the door today?

— Write your question on your note card

— On the other side of your card, write your name

— When you are done, raise your hand or catch Andrew’s eye so he knows

[Full notes from this workshop session are available on this google doc, or for download as a Microsoft Word document]

Part 4: Conclusion and Further Reading

Many disability studies scholars have pointed out that the phrase Universal Design sounds utopian. There is no way to truly anticipate all possible users and their unique abilities, vulnerabilities, and needs. Jay Dolmage has described UD as an approach, “[a] way to move” (2015). In that light, I encourage you to continue thinking about the ways your course design might invite the widest possible range of users. Try experiments in flexibility and multiplicity in your assignment design, course policies, and communication practices. Below are some useful resources to get you started.

Jay Dolmage, “Universal Design: Places to Start,” Disability Studies Quarterly 35:2 (2015): http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/4632/3946

This short article defines UD approaches and imagines how they apply to our roles as college-level instructors. It also includes a 20+ page appendix of “places to start” for implementing universal design in a wide range of classes, including lecture, discussion, seminar, and lab-based classes.

Patricia Dunn, Talking, Stretching, Moving: Multiple Literacies in the Teaching of Writing, 2001

This book includes excellent assignment ideas for engaging students in diverse learning practices, including play-acting, analysis using picture drawing, hands-on rhetorical outlining, and other techniques that help students with a wide range of cognitive skills succeed at writing. Good to get from ILL, copy out a chapter or two, and try out experiments during the term.

Disability Rhetoric, www.disabilityrhetoric.com

This website serves as a network for composition/rhetoric scholars who work in disability studies. It contains bibliographies, sample syllabi, and a wealth of other resources.

Institutional Archaeology: What We Learn By Digging Up Dead Programs (CWPA 2015)

I presented this talk on July 17, 2015 at the annual conference of Council of Writing Program Administrators in Boise, Idaho. I would be grateful for feedback, either as comments to this post, or via email at a.j.lucchesi@gmail.com

In the last few years, WPA studies has begun to look seriously at the challenges of improving access to students with disabilities. This is in no small part because the growing movement Disability Rhetoric movement has produced innovative scholarship that show how disability issues are central to our work as writing instructors and intellectual-bureaucrats.

For instance, scholars like Patricia Dunn, Melanie Yergeau, and Margaret Price have shown how writing curriculum and classroom practices can be built to accommodate the full participation of all students. Or how, if unchanged, they exclude many kinds of students.

Others have taken a broader institutional look outside the writing classroom. Jay Dolmage, for instance, has critiqued the current prevailing model of disability access in North American higher education (“From Retrofit to Universal Design,” 2012). Under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, all federally funded institutions of higher education are required to provide so-called “reasonable accommodations” to ensure the full access and participation of persons with disabilities.These accommodations, which are traditionally administered by a disability services director, are meant to ensure disabled students do not face unlawful barriers to their success, for instance not being able to access library resources, get to and from classes, or take exams in an appropriate environment.

The problem is that the accommodation model, Dolmage argues, works as a retrofit, offering only the minimum required alteration to what is fundamentally an exclusionary institution. The changes disability directors are authorized to make are one-offs, applied only to one student at a time. Seen in this way, it is we as writing instructors and program administrators who have the power to make the most change in the disability landscape, not by making one-off changes, but by fundamentally re-designing our programs to better allow full, diverse participation.

I want to talk briefly about my dissertation research and how I’m hoping it will contribute to the work of Disability Rhetoric. With the exception of Brenda Brueggemann’s work on the history of Gauladette University (1999), much of our theory has taken the present as its focal point. Our field’s history of disabled students at mainstream colleges is fragmentary at best.

One significant reason we know so little about the history of disability in higher education relates to Mark’s conception of institutional amnesia. Most of the history of disability access work on campuses has passed unrecorded in our institutional archives. In part this is a willful omission, because, at least in recent times, disability labor is done confidentially. However, it’s also because most of the labor itself was hum drum: one part bureaucratic, finding funding to pay students to read for their blind peers; one part personal, counseling students how to deal with a bigoted instructor. Except in rare cases, almost no paper trail exists in official institutional archives.

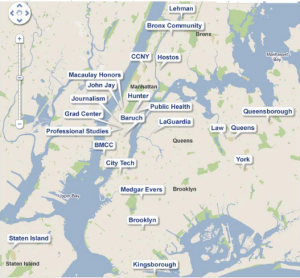

My research focuses on the history of disability-specific programming in the City University of New York system. CUNY offers a compelling object of study for a number of reasons. First it has one of the longest histories. In 1946, it developed one of the first programs in the nation specifically aimed to integrate disabled students in a mainstream college setting. This program, begun to provide college access for wounded veterans returning from World War II, was at the cutting edge among the handful of other such programs around the nation. This program predates the earliest disability-access laws by nearly thirty years, and thus offers a rare snap-shot of the early attitudes about disabled students and their education.

CUNY also affords a wide scope in terms of institutional diversity. Since CUNY is comprised of seventeen teaching campuses, each campus has its own independently operated disability services office. Each is attuned to its individual campus character, whether that be a community, four year, or graduate campus. Each campus has a legacy of specially designed programs. Some of these proliferated and spread around the system, some of which died out within a few years. Each campus keeps its own institutional archives, though, naturally, there is vast inconsistency in terms of what records are kept by each archivist and whether disability issues get a folder. For instance, I have yet to find any materials related to disabled student clubs and organizations, though I know for a fact they’ve existed for at least twenty years.

Oral history provides a key to unlocking much of this history. So far, I have interviewed thirteen current or former disability service providers from across the CUNY system. My informants range from people who began working in the field within the past academic year to those who worked on disability integration in the mid 1960s. One informant, whom I only identified a few weeks ago, was actually a student who graduated through that early program established in the ’40s, who later went on to direct the disability office at his own alma mater.

In addition to informing me about the nature of their work as service providers, these informants also give me important information about the attitudes toward disability and access held of students, faculty, and other branches administration of their home institutions while they worked there.

CUNY’s unique multi-campus structure created a kind of incubation chamber for sharing ideas about disability access. Those of us who know CUNY’s history of basic writing scholarship will be familiar with how the SEEK program Sean just described and the system of basic writing fostered scholars like Kenneth Bruffee, Mina Shaughnessey, Sondra Perl, and many others. These scholars shared their work through informal networks around the CUNY system, learning from one another before spreading their work publicly. CUNY service providers did the same, forming a coalition of administrators in which they could share ideas, developed best practice guidelines, publish scholarship, and organize for public engagement, both at the campus and at the state level.

It is partially because of the close personal connections formed within this coalition, called COSDI, the Coalition on Student Disability Issues, that my research has been possible. COSDI members who are now reaching retirement are eager to get on record the important work that they did over the years. Additionally, many of these individuals kept personal archives of their work, materials not available in any official collection.

One of my aims in this research is to use the programs that were developed to serve disabled students at different historical moments as a lens to better understand these students’ institutional position. I’ll explain what I mean with a few quick snap-shots from my research so far.

As I said, the 1946 program housed City College (then known as the Uptown campus), was initially designed to grant access to wounded veterans. In fact, an influx of wounded vets didn’t materialize, and the program instead oversaw the admissions of a few dozen disabled civilians each year from 1946 to the mid 1960s. In general these students had either sensory impairments or chronic health conditions. The campus was closed to students who use wheelchairs. There was at this time, of course, no popular concept of learning disabilities.

In some ways, this early program resembles modern disability services programs. Students were assessed by college staff and received special help with registration. The students’ instructors received a kind of accommodation letter, just like today.

However, unlike modern disability services, the program was designed to serve people recovering from wounds, and so the entire enterprise was suffused with a highly medicalized view of the students and their educational needs. In order to gain admissions to the college, students were subject to examination by the Health Guidance Board, a group of faculty, administrators, and physicians who, according to the college bulletin, were authorized to determine “whether they could profit from college training (Bulletin 1968/69)” before granting them access.

The Health Guidance Board’s mission went beyond simply assessing students for admissions. According to one institutional document, the Board also worked to “[effect] adjustment to the maximum correction of physical defects” in the students. The most widely publicized aspect of this recuperative mission came from a four semester series of special physical hygiene courses disabled students were required to take. Instructors in these PE courses were briefed on students’ health conditions and charged with designing each student an individualized rehabilitation plan, with biannual reports on their progress made available both to the Health Board and to “all instructors interested in the health of the student.” (I should note that four semesters of PE were required for all students at this time, but only students overseen by the Health Guidance Board were subjected to these special sections.) We can think of this program, described as (quote) “the reconstructive education of the physically handicapped [which is] concerned primarily with the prevention and correction of physical defects” as, perhaps, remedial courses in normative embodiment.

This early program reflects, in many ways, the medical model of disability that dominated before the advent of the disability rights movement in the 1960s and 70s. In this model, disability is thought of as an individual problem, a defect located in the body. As the politics of disability changed, disability programs began to shed some of their medicalized perspective—where disabled students essentially lived as patients of the university—and instead began to align with the social model of disability. Within this model, disability is understood as a problem of social oppression, not a problem of physical defects. This logic argues that disabled people don’t need curing, they need the same level of social access and resources afforded to the able-bodied majority, and laws passed in the mid 1970s asserted that these resources and affordances were, in fact, their right. Programs developed during this period tend to bear the marks of this political alignment, most notably the Distance Education Program for the Homebound, which I can tell you about in Q&A. Obviously, for those of us interested in the history of basic writing, we can hear a lot of resonance in this political shift from seeing disabled students as broken or deficient to seeing them as people disenfranchised by oppressive social systems.

To conclude, I want to turn my attention to another program from CUNY past. This one I know about entirely based on personal interviews and a pile of personal documents generously donated by my informant.

By the early 1980s, CUNY was receiving an influx of a new kind of disabled student. These were students who had come up through the public K12 system under the purview of federal Public Law 94-142, then called the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which was passed in 1975. This law mandated that whenever possible, disabled students should be taught in mainstream classrooms (“Least Restrictive Environments”). The law provided individualized education plans (IEPs) designed to help integrate students across a wide range of disability categories including learning disabilities, psychiatric impairments, and other kinds of invisible disabilities. This period coincided, of course, with the rise of psychological and cognitive testing in public schools, and the massive increase in diagnoses of learning disabilities, attention disorders, and other psycho-social impairments.

In the late 1980s, Anthony Colarossi had been working as a school psychologist in an especially poor area of Brooklyn and advising the board of education about Learning Disability issues. He came to Kingsborough Community College both as the director of disability services and as a member of the psychology faculty. Under his direction, the college developed a new link between counseling and disability services. He also developed a resource center for learning disabilities that became a national model.

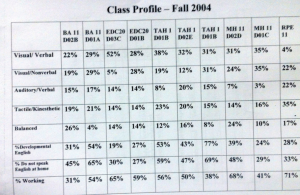

I want to look closely at a program Colarossi developed in the early 2000s. Based on a model pioneered at UC Berkeley, Colarossi designed a two-semester special section of the college’s Skills Development courses specially suited to students coming to the college with disability diagnoses. The courses only ran for three years, and in all only 118 students passed through the sequence. However, Colarossi kept detailed records of the courses, including student writing, class materials, and results from a survey administered to students in the course.

Most of the students in Colarossi’s course were also students we’d know as basic writers. For those who didn’t come to college with a diagnosis, many were flagged for his attention because they had failed the CUNY writing exam multiple times. Historically, this period in which psycho-social disabilities became firmly situated within the work of disability services represents an important moment for the definition of basic writers. Now there was a special population within the broader community of basic writers who, because of medical diagnosis, held a different institutional position, which included access to specialized services. For students with the disability label, Colarossi’s class offered a useful space for supplementary literacy instruction as well as a venue for psychological treatment and identity development.

The first semester of the sequence centered on their experience as students adjusting to college life. In essence, it’s a writing course. In order to help students resist feelings of alienation, they choose a favorite spot on campus as their journaling spot and write weekly entries reflecting on their progress and hardships as a student. These weekly check-ins are then revised into a final narrative essay. They also study the nature of their own disabilities, a unit supported by lectures and activities about different learning styles, multiple intelligences, and other topics from the clinical side of the learning disability field. In another project, students write about the other courses they are taking, reflecting on how the instructors’ teaching style works with their own learning style. The course culminates in a final written exam, where students are asked to synthesize what they’ve learned in writing, explaining the nature of their disability, their personal experience of it throughout their lives, and their perspectives on themselves as students. The second semester, which Colarossi had fewer materials from, focused on vocational and career issues. Students were asked to investigate a career path and major, interviewing professionals in the field and reflecting on its appropriateness for their skills and weaknesses.

Throughout these courses, Colarossi employed pedagogy we would recognize from our own field. Students used freewriting in their journals. Students shared drafts and gave oral feedback, in this case in a kind of group therapy setting (which is, after all, the basis of many Process Pedagogy peer review practices). Throughout the course, students work to develop a meta-cognative awareness of their own thinking and learning styles, and to choose work habits that work best for them.

I should say that although Colarossi’s methods may seem more familiar to our own and certainly more benign than the paternalistic curative model I described earlier, from a disability studies perspective, there are still some troubling aspects of Colarossi’s approach. Students in this class were, ultimately, clients of the combined disability and counseling services. Their assigned counselor got updates on their progress in the course. Indeed it was taught by two employees of the counseling and disability services. For this reason, it still took a kind of rehabilitative bent toward disability integration, in that the course was designed to work through many of the challenging psychological aspects of surviving a college education with a diagnosed disability. It wasn’t a course designed to cure defects, however. Rather, the course offered a medical understanding of learning differences to the students, but it also situated it within a culture of disability bias and helped students deal pragmatically with social limitations created by one-dimensional teaching and restricted career choices.

To conclude, I want to urge us to think about how we as a field are responding to the challenges of creating accessible programs today. What are the current beliefs about disability and access that are motivating us to approach this work as part of our mission as writing teachers and program designers? As we as writing teachers and program designers accept that our programs should help promote disability access, we should consider the politics underlying those efforts. Just as these dead programs I have found lost in CUNY’s history reveal something about the politics of disability in their time, our own programs will reveal how we respond to the challenge of equal access.

Works Cited

Brueggemann, Brenda Jo. Lend Me Your Ear: Rhetorical Constructions of Deafness. Gallaudet University Press, 1999. Print.

Dolmage, Jay. “From Retrofit to Universal Design, From Collapse to Occupation: Neo-Liberal Spaces of Disability” presented at the Society for Disability Studies conference, 2012. Accessed from Academia.edu on July 17, 2015. http://www.academia.edu/1244157/_From_Retrofit_to_Universal_Design_From_Collapse_to_Occupation_Neo-Liberal_Spaces_of_Disability_

Conference Presentation, CCCC15: Memories of “Subtle Triage”

This talk was presented at the Conference on College Composition and Communication in Tampa, FL on March 19, 2015. It is part of panel E.24, titled New Directions for Disability-Studies Research: Using Mixed Methods to Appeal to Wider Audiences in Higher Education.

Memories of ‘Subtle Triage’: Histories of Academic Disability and Institutional Practice

Today I will be discussing research I am currently undertaking to study the evolution of disability-specific programming and administrative work in the nineteen-campus City University of New York system. My aim in this study is to use oral history and archival analysis to reconstruct the history of disability access programming going back as far as the mid 1970s, when the first pre-Rehabilitation Act programs began.

By paying close attention to the programs developed in the name of “disability access” throughout CUNY’s history, I hope to track the ways institutional beliefs about disability as a concept or disabled students as a population may differ across different time periods and institutional contexts. I hope understanding this history will help administrators, including writing program administrators, better understand the forces at play when we confront our institutions on issues of disability.

Since I am still very much in the midst of my research process, my aims for today’s talk are fairly modest. I’ll begin by discussing my own take on this panel’s theme, discussing what makes my project disability studies research (as opposed to simply a study about disability). I will then outline my methodology and present a few early findings that are just beginning to shake loose from the data.

So, what do I mean by describing my approach as disability studies methodology? As my co-panelist Margaret Price has observed in her chapter on DS methodology (cite), there is no singular, monolithic approach that characterizes disability studies. As an interdisciplinary field, we draw together a wide range of methods and discourses.

What unites disability studies research, then, is a stance toward the notion of disability as a concept. Rather than seeing disability as a purely medical phenomenon, we in DS investigate the social and cultural factors that affect the lives of disabled people. For us who work in colleges and universities, this stance leads us to investigate the lived experience of disabled students and faculty, to better show the normalized academic practices that impose barriers for full access. In this way, we see how factors like curriculum design, technological tools, teaching practices, hiring and promotion procedures, time-to-degree schemes, even admissions policies–how all of these features built in to the institutional fabric of our colleges and universities–contribute to how accessible or inacessible these environments are.

One central aim, I hope, of DS research in higher education is to find ways to make our institutions more accessible to more people, to find better approaches to promoting access than the ones tried in the past. My aim in this study is to track back in the historical record to the first programs designed to serve disabled students within CUNY, the nation’s largest public urban university system, and to unpack the beliefs about disability and academic life central to those early efforts. By comparing these early programs with later ones, I hope to track what changed within the institution’s stance toward disability, particularly as the field of disability services in higher education gained professional ascendancy and accommodation practices became more standardized.

The main bulk of my data for this study comes from interviews with approximately fifteen disability service providers from around the CUNY system. I am speaking with providers from all three kinds of CUNY campus: two-year, four-year, and graduate campuses. I divide my informants into three generational groups. The first generation began working in CUNY in the 1970s, either before or soon after the passage of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which actually came into force in 1978. A few members of this generation are still working in the system, but most are now retired. I am demarcating the second generation by their proximity to the passage of the ADA in 1990, so folks who started in the late 80s and early 90s. The third generation began their work in the last ten to fifteen years, including some who began only this year.

My interview process has two main stages, individual interviews and focus groups. I am using the initial interviews to discover the scope of history my informants know, but also to draw out potential topics for the focus groups.

My interviews, which last approximately 60 minutes, break into five groups of questions. The first group focuses on subjects’ professional history: when and where they started the job, their professional training, the major they undertook as a program director. This category provides me the most useful historical coverage to fill in my timeline. My second group asks about how they see the role of disability service provider working within their local institution: here I ask about how they negotiate campus politics and relations with other branches of the administration. Third I ask them to describe from their perspective the work of disability service directors–what they see as the necessary skills for a director, what are the major hurdles, and (this turned out to be a useful question) whether they see the role as primarily activist or primarily administrative. Fourth, I ask about their relations with faculty. Finally, about their perceptions of students–who their students are and what barriers they believe students face. One of the things I learn from these last two sets of questions is how faculty/student relations differ from campus to campus, as well as how different campuses have come to specialize in providing different kinds of access or access for particular populations.

At this point, I am a bit more than halfway through my interview process. I’ve spoken with ten informants representing all three campus types and all three generational groupings. There are still some folks central to the history who I haven’t been able to get ahold of yet, but I’m optimistic.

In the rest of my time today, I want to give a quick taste of what is emerging from my interviews and how I am deriving the topics for my focus groups. If time allows, I will also discuss my archivization process and some quick impressions of where textual analysis fits into this study.

The first service provider I spoke with was a person I’ll call for now Subject 1, a first generation service provider who began her work who in 1976. Coming with a background in social work, she administered a grant-funded program at Queensborough community college called the “homebound college program,” a distance learning program for people with severe mobility impairments. Since she began in the system before Section 504 came into effect, she witnessed the formalization of the disability service director role and the formation of the cross-campus disability directors collaborative, COSDI, the Committee on Student Disability Issues, which engineered many of the programs over the last four decades.

Subject 1 had a particularly strong response to my question about whether she identifies as an activist and how that perspective comes out in her work. She identified strongly as an activist, noting that she had been involved in the independent living movement in Queens for many decades. In explaining how she sees her work as activist, she told stories about efforts she and other COSDI members made to lobby the state legislature to secure a stable funding line for disability services in CUNY during the 1980s, which to that point had only been funded by temporary grants. She described the way she and her first generation colleagues helped form student disability activist groups, which could agitate for change on campuses in ways the service directors couldn’t, for example when the group S.O.F.E.D.U.P. at Brooklyn College filed a civil rights lawsuit over inaccessible buildings. When Subject 1 claimed the title of activist, she spoke of direct action work to change policies both inside and outside the university, and she spoke of the importance of activist techniques, including public organizing and deft use of legislative bureaucracy to enforce change.

I want to compare Subject 1’s perspective to a second-generation service provider. In the early 1990s, Subject 2 was a student at Queens College, a four-year college closely connected with Subject 1 Queensborough Community College, and an activist in one of the disabled students groups Subject 1 generation began. When he graduated in 1993, the disability services director position at the college was empty, so he took it as his first job out of his undergraduate sociology program.

His work as a student disability advocate led him to receive special training in ADA issues in higher ed, and he brought this expertise to developing new programs at Queens. Six years ago, however, he left Queens College and became the director of disability services for the CUNY Central Office, and now he oversees policy and initiatives for the entire system.

Obviously, Subject 2 spoke about the importance of student advocacy groups. However, he had a strong aversion to aligning disability service provision with activist work. In his view, service providers’ position in the institution forecloses an activist alignment. I quote:

There are moments where you assume the mantle of activist. If you look at the way in which the role is best situated, best positioned, you’re striking a balance between advocating for students in terms of removal of barriers and level playing-field, but also advocating for the rigor of academic standards. So I guess if you’re activist, you have to be activist for both. If you’re activist too much for one or the other, you’re not doing your job well.

I heard in Subject 2’s interview a real ambivalence on this point. As a central administrator, his job is to ensure stability of services and to maintain the support of the broader administration for his work in access programming. And under his directorship, the Central Office has instituted some impressive CUNY-wide programs, including a job mentoring program for disabled students that has been nationally recognized. However, he admitted a little later in the interview that if I’d asked him the same question about activism a few decades earlier, when he’d started as the director at Queens, he probably would have answered very differently.

What I’m trying to show here is the way my exploratory interview process is helping me develop the focal points for my eventual focus groups. Activism, or the providers’ beliefs about how activism works in relation to disability services, is emerging as a powerful problematic for this population, an issue that divides their perspectives–sometimes along generational lines, but perhaps according to other factors I will discover in the focus groups. A third generation disability director at a community college in the Bronx, for example, whose background was in business administration, hesitantly claimed the activist title, but in describing the work she considered activist, mostly discussed disability cultural programming she had developed–film series and disability awareness events. Others see the role they play in getting faculty to accept student accommodation requests as their primary form of activism. Some don’t claim the title at all.

Other key themes are emerging as possible topics for further analysis across generation and campus affiliation: The role of technology for disability services is obviously key. Likewise, I’m finding interesting divided opinions on issues related to academic standards and testing, which is a contentious issue given CUNY’s history of open admissions and legacy of high-stakes gatekeeping literacy tests.

Before I close, I’d like to briefly outline how I am using archival research and textual analysis in this study. Since the history of disability programming in CUNY is so scattered and so poorly recorded in authorized archives, much of my materials are coming from the service providers themselves. Many of the first generation have maintained small private collections of documents from their work, and they’ve been generous enough to give them to me for my study. (I should say here that one key reason why this study is working at all is that the CUNY disability services community is actively interested in getting this history documented before it’s forgotten.)

Like my focus group methodology, the archive process tends to feed back through the initial interviews. In every interview I do, I learn about two or three now defunct CUNY programs I wasn’t aware existed, which I can then follow up on, both with my informant in followup interviews and in the local campus archives, if any evidence exist there.

Based on what I’ve found so far, I am in the process of developing a taxonomy of the kinds of texts these service providers have produced as part of their role. In one sense, these documents help me reconstruct the details of the history overall, but they also help me understand the ways service providers use rhetoric to achieve their ends. Especially interesting to me is how they justify the value of their services to different stakeholders, and the ways they leverage established beliefs about disability to get their way. In my taxonomy, I try to group together different rhetorical situations:

First is performative institutional discourse: things like grant proposals, programmatic assessments, funding requests, and other texts that show DSPs using rhetoric to work within bureaucratic systems. These are the most common texts I have access to, often because they’re kept as public record.

Second is dialogic administrative discourse: these are things like correspondence between DSPs on different campuses, minutes from COSDI meetings, conference proceedings, and other texts that show service directors sharing practices and debating ideas about disability and access among themselves.

Third is informational public discourse–materials the DSP produces to provide information to the public, to students, to faculty, to parents about disability and access. This is by far the most prolific kind of discourse, but it also tends to be ephemeral. Examples here are pamphlets, flyers, websites and the like.

Finally, performative pedagogical discourse–this category attests to the fact that many service providers have developed unique curricular programs on their campuses. A compelling example I am trying to find more evidence about is a program developed by a LD specialist at another community college that ran a two-semester (credit bearing) academic skills and self-advocacy training course for at-risk students with disabilities. The program is now defunct, but I’m curious to see how its approach to literacy skills training and disability advocacy might align with work in our own field toward disability studies inspired writing courses.

It’s too early to tell what kinds of questions I’ll be able to ask of these texts once I’ve got them. One key question pertains to the ways disability programing is justified. When speaking to different populations and in different political climates, how likely are DSPs to invoke the legal mandate for access, as opposed to invoking a value-added justification for disability inclusion? How likely are they to invoke rhetoric of diversity? Likewise, I am deeply interested in how questions of academic standards are policed in these documents.

I will end there. I would love to talk more with you all after the panel if anyone has ideas or questions about my project. I look forward to reporting more as things continue to develop.

Works Cited

Kerschbaum, Stephanie L. Toward a New Rhetoric of Difference. Carbondale, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 2014.

Price, Margaret. “Disability Studies Methodology: Explaining Ourselves to Ourselves.” Practicing Research in Writing Studies: Reflexive and Ethically Responsible Research. Ed. Katrina M. Powell and Pamela Takayoshi. New York: Hampton Press, 2012. 159 – 186.

—–. “Access Imagined: The Construction of Disability in Conference Policy Documents.” Disability Studies Quarterly 29.1 (2009).

I’ll have a dissertation prospectus with club sauce

This week was about trying to get back in the swing of things after my post-orals pause. The big challenge has been to get a stable writing routine going. I haven’t been completely successful. It’s difficult not having immediate deadlines to work toward, and to only have a vague sense of the path I need to be taking as I inch dissertation-ward.

1. What is a dissertation prospectus?

I decided to focus my attention this week on wrapping my head around the dissertation prospectus. Every program’s definition of a dissertation proposal (as they’re usually called) vary substantially in terms of size, structure, and constraints. The GC English program has only a few guidelines:

- It must be under 10 pages, double spaced

- It must”provide a compact, concise blueprint for a dissertation by including:

- An overarching perspective on a specific project that can accommodate substantial inquiry;

- A brief description of path-making commentary immediately relevant to the project;

- A series of chapter titles and thumbnail descriptions of them.”

- and, it must have a working bibliography.

Beyond these basic parameters, the genre is quite open. In some ways this is encouraging, because I could imagine checking these boxes in any number of ways. However, I know better. Open prompts are nice in structured work environments, where help and guidance is easily available. But when not paired with structure–like when I have nothing but free time and nobody checking in on me–they’re the express route way into the mud pit.

What the program has provided here is a menu–generated by the client who will do the eating, a list of what they expect to be served. What I want is a recipe–generated by the chefs who will do the cooking, a list of the major ingredients and the essential techniques for preparing them. The recipe and the menu are related, of course. But there’s a big difference between ordering a cheese soufflé and making one.

This semester, I joined on to a dissertation workshop, in part because I wanted to see how other apprentice chefs are doing their cooking. It’s no credit, and fairly low intensity in terms of time commitment, but I’m hoping it will help get things moving on my writing. In our first feedback session, we ended up talking about our writing goals for the semester, which, for most people, included drafting a prospectus. We were all desperate for recipes. The professor leading the workshop seemed hesitant to give one, so he gave us only some general proportions:

- 5 – 6 your summary of previous scholarship, identifying the gap you will fill, and explaining how you will fill that gap

- 3 – 4 pages for your chapter summaries, each chapter focusing on an “object”

This breakdown helped a bit: rather than simply naming the things on the plate, it describes plating and portion size. It still doesn’t tell me what to do with the whisk in my hand, however. I understand why there aren’t a lot of recipes out there. We’re all doing different sorts of projects, and we all have wildly different writing practices. One model won’t fit everyone.

I decided I wanted to do some more digging to figure out what kind of recipe would work for me. So, first, I had to eat.

* * *

2. Reverse-engineering a Dissertation Prospectus

I put out a call among my more advanced colleagues, asking them to send me copies of their accepted prospectuses for me to study. I limited myself to folks who work in my area of English, composition and rhetoric.

Each of the three studies works with Comp/rhet methodologies ranging from ethnography of a writing center to quantitative analysis of our field’s published research. These projects are quite far from the kinds of literature-focused studies the other folks in my dissertation workshop are doing. They are, however, very close to the kind of mixed-method, interdisciplinary study I’m working on.

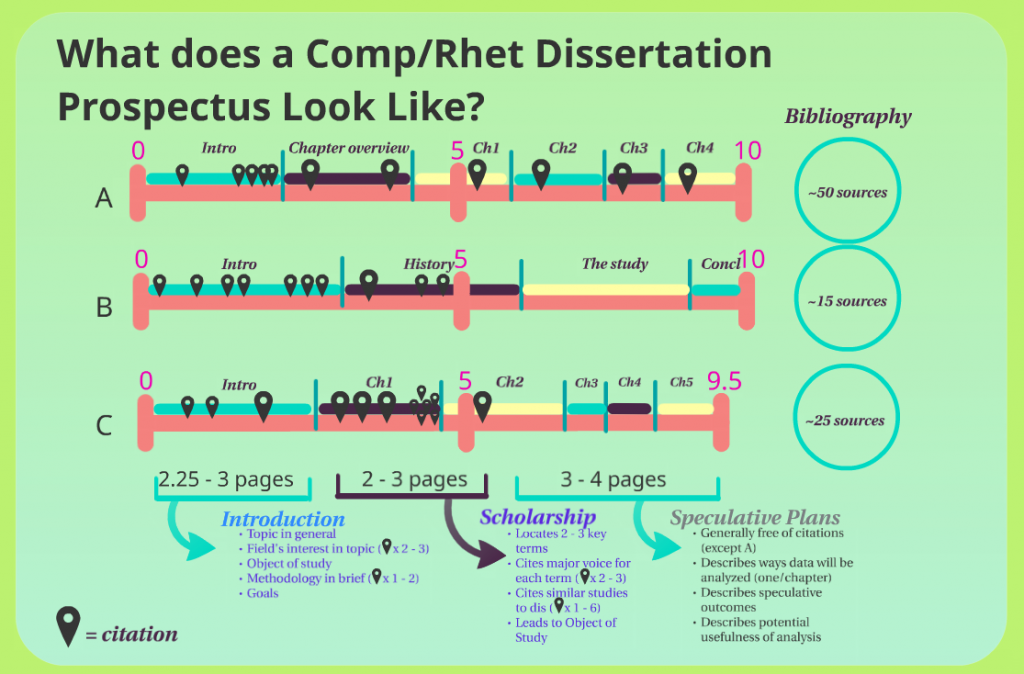

I read through each of the prospectuses, creating a reverse outline for each paragraph, noting the overall function of the paragraph, the ways citations were deployed, and the way they discussed the project. Here is a visual representation of my data:

[Note: This data is in now way scientific. Sizes of things are guestimated to give rough proportions.]

Some observations:

As you can see, none of these three prospectuses follow the plating arrangement recommendations of the dissertation workshop director. Two of them (A and C), in fact, devote over 2/3rds of their time to discussing the chapters. One of them (B), discusses the chapters almost not at all, instead devoting most of the draft to methodology talk and shoving a very speculative chapter outline into a single paragraph in the “conclusion” section.

A and B both take the approach of providing a very quick chapter overview somewhere in the first third, near the end of the introduction section. They then devote the rest of the prospectus to an in-depth talk through of the chapters, for each chapter summarizing key scholarship that lays the groundwork for that particular chunk of the analysis.

By the half way point of the prospectus, the focus shifts from what scholars have said to what the researcher hopes to do with the data that will be gathered; naturally the mood shifts from indicative to subjunctive, from what X or Y says in the literature to what the researcher hopes to do or thinks might happen.

Model A is the outlier here: Rather than getting all the secondary references out of the way early, each chapter description includes a citation to a foundational study from which the author derives on principle or key word that is the focus of that chapter. Essentially, a call-and-response format, where the call comes from one important researcher, and the response comes from the researcher’s attempt to use/expand that researcher’s method.

In some ways, Model A comes off as less confident, because it is shorn up by scholarship every step of the way, compared with B and C, which devote more effort to describing their own original research design. A feels more grounded and safe, where B and C feel more experimental and speculative. I wonder what these different approaches say about where the authors were in terms of their data-gathering processes . . . I wonder where I’ll end up falling on this spectrum . . . .

* * *

3. Revised ingredient list

Of course, looking at products won’t tell me exactly how they’re made. Still it helped me get a better sense of the ingredients I’m going to need to actually prepare my dissertation prospectus. So, to make a prospectus, it looks like I’ll need the following:

1. A few citations that attest to the field’s (or general) interest in my topic: these can be from popular or scholarly sources, but they should make the topic seem current and important.

2. A paragraph of enticing, broadly phrased questions that folks in my field want answered–to be deployed at the end of the intro and the beginning of the conclusion.

3. A description of the object of study I have chosen and what makes it unique.

4. A narrative of my data-gathering and analysis process, broken into four or five speculative steps.

5. Two or three big citations that justify my methodology. These can come from outside comp/rhet proper, especially when using social-science-influenced methodologies. These are citations as models.

6. Four or five smaller citations that establish a gap in other studies: these come from other comp/rhet studies that are similar in some way to my own, but that leave an opening for my study as a corrective/extension. I only need to mention these, not explore them as models here. These are citations as clamor.

7. A paragraph of enticing speculative uses for the answers my study will produce. These are to be deployed in the conclusion, but also hinted at at the end of each step of the research/analysis chunks.

Some of these things I have; some of these things I don’t.

Based on all this thinking, I’ve decided that my next step should be to break these sections down and tackle them one by one, perhaps devoting a week a piece to each of them. First, I think, will be the object of study. I need to be contacting more interview subjects and looking over the archival materials I’ve started gathering, so this feels like a section that is still a bit out of my reach, but, with a little stretching, within my grasp. And it should pave the way toward the methodology stuff, which is my shakiest territory.

Any of you cooking along with me at home? Feel free to share your recipes here.

Distinct from what, exactly? Clearing the post-exam air

So, I passed my oral exams. I did some last minute cramming, reading reviews of the books I didn’t get to and re-reading my notes on some key texts I knew my examiners liked, and ended up earning “distinction” for my performance.

I don’t give much weight to this ranking, really, though others seem to. I know from my time on Executive committee that between 70 and 80% of students who pass the orals get distinction, making it pretty meaningless. In effect, the only thing the ranking does is make anyone who doesn’t earn distinction feel shitty about merely earning a “pass.” In fact, I am one of the last students who will ever earn distinction on this exam, since the program just voted to ditch the ranking. Not to say I’m not proud of my performance, but just to say that my pride is heavily salted.

Now that hurdle is jumped. This week I made my first attempts to get a stable working/living pattern going. Since I’m not teaching at the moment, my only professional obligations are working as a Quantitative Reasoning fellow at Hostos Community College two days a week, 9 – 5, and doing occasional Communication Fellow work by appointment at Baruch. This leaves me lots of time to be writing: writing a dissertation prospectus, writing conference proposals, writing the CFP for a special issue of the Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy I’ll be editing, writing poetry and emails and posts for this here blog.

I’ve drawn up a provisional schedule that has me writing for at least two hours a day, five days a week–usually in the morning, usually followed by or following the gym. I’d be curious to hear from others how you manage your day to day writing schedule in this post-coursework, post-exam limbo called the dissertation stage.

I am anxious about entering this self-directed writing portion of my degree. I haven’t kept a self-sustaining writing practice for quite a while: usually I write to deadlines only. So, having time set aside for writing nearly every day, making writing my primary job, represents a substantial change in my routine. I think it will be good for me, but it will also mean I have to confront my writing demons more regularly.

This morning was my first long writing session. Since I’ve taken the post-exam week to rest my academic brain, I didn’t end up writing anything dissertation or scholarship related. Instead, I spent some time writing some poetry about a dream I had while I was in Spokane, Washington for my brother’s wedding last weekend. Naturally, it’s just a quick poem and would need substantial revision if I wanted to keep working with it, but I thought I may as well share it here. Feedback, as always, is welcome.

Tree Dream

I know that trees are dangerous. Sonny Bono, for example, died

after skiing into a tree. I look at the concave hollow around the tree’s trunk

where the canopy’s shadow blocks the snow and know he laid there

unseen and injured and sad for who knows how long.

I am alone now with one tree among many in a shallow scoop

of mountain, and as danger does, it beckons.

My skis are off, anchored upright in the snow behind me.

The tree has shed its lowermost branches for me, cauterized,

clear to my head-height a smooth column.

I lean my mittened hands against the trunk, testing our weights.

My palms pivot outward, beginning a slow embrace:

press with my forearms, then my bent elbows around to its sides,

then flat chest to chest, turning my head to the right to protect my nose.

I am shocked by the chill bark against my neck and left ear.

Would we were all so quietly alive.

I grip harder as the tree takes to the sky, pulled upward

as if by the tweezers of heaven and cast loose in the wind.

With the ground falling away, my legs wrap tight too,

my sensitive groin pressing in, ankles locked together.

As the updraft floats us down the mountainside,

I imagine my brother and father’s befuddled bodies

poised, pointing upward, below me. They stand

on their skis side by side with my abandoned gear and seem

with their poles as if to wave me down or wave goodbye.

I can only nod, pressed as I am to the trunk, holding on for life.

I didn’t know I had wanted relief from the ground.

What a gift–from this tree whose embrace accepts me

as it would a nail, apathetic and secure.

I have married this dangerous tree. We will all of us be missed.

A year of reading, what’s it good for?

This is a draft of my 10-15 minute introduction, which I will present at the beginning of my oral exams tomorrow. Comments are welcome before 9am on Wednesday 10 September 2014.

Rather than spending this time at the beginning of my oral exam describing my three lists to you again, I thought I would talk a bit about my motivations in putting them together and how this exercise has been useful to me so far. I won’t go much in detail into what I learned from reading the individual texts (since that will certainly come up as I answer your questions); instead, I want to focus on practical concerns, on next steps based on what I know and don’t know now, on real world applications for all this thinking I’ve been doing. So, having spent a year or so reading, what’s it good for?

My motivation in putting these lists together was to help me get the scholarly acumen to pursue my personal commitments as an activist scholar. My own perspective as an activist scholar emerges from three different but related images of myself:

First, I see myself as a cultural theorist. I have a long history of work in critical race studies, feminism, and queer theory. Disability studies offered me a natural extension of my interests in social and cultural analysis, a new way of asking impertinent questions about what we think we know and how we have agreed as a society to operate.

Second, I am also a writing teacher, a worker within the contentious and pervasive institutional mechanism of literacy instruction that extends through nearly every college and university in the nation. This field offers me new ways to understand the importance of writing and education for adults, and it also gives me practical knowledge of how universities work, especially from the perspectives of writing program administrators, writing across the curriculum directors, and other hybrid faculty/administrator roles that folks like me tend to hold, often immediately after earning our degrees.

Finally, I am a person with learning disabilities who has chosen to make academic work his career. I’m someone who has difficulty carrying out the tasks of academic life for reasons believed by some to have root in my atypical brain–specifically my dyslexia. I am personally invested in understanding the kinds of challenges people like me face working in academia as it currently exists; and I am personally invested in imagining ways people like me–people we might call “neurodiverse”–can play an active role in changing the status quo of teaching, learning, and working in colleges and universities.

So, the purpose of this exam for me has not been simply to gain knowledge of a set of canonical texts for their own sake–it’s been more about utility. My aim was to get the lay of the land, as it were, for how currently published scholarship can support me in my commitments as an activist scholar.

My reading led me to some well-laid paths: for example, it led me to a robust body of scholarship by disability studies scholars in the humanities published over the last twenty-plus years. Likewise, it led me to the works of writing teachers and writing program administrators who, since the days of Open Admissions in the late 1960s, have been imagining new ways literacy instruction can support the success of students at odds with academic environments because of racial, ethnic, gender, and class differences.

It also led me to relatively obscure paths, especially in trying to better understand learning disabilities and other disabilities associated with neurological difference as they are experienced in colleges and universities. Here I had to draw upon a wide range of discourses from fields as diverse as neuroscience, psychology, educational technology, as well as the first-person accounts of memoirists and former students.

I still don’t feel I’m an expert in the topics I studied for this exam. While I have a much better lay of the land of what others have written, and while I feel I have grown much more conversant in the discourses of disability, learning, and teaching in higher ed, I still feel anxious about the gaps in my knowledge.

For instance, I still know very little about the history of disability accommodation practices on college campuses following the passage of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation act of 1973, an important landmark moment for disability in higher ed. Likewise, I don’t know, exactly, the rates at which LD or other neurodiverse student populations end up in remedial writing programs, or the ways their experiences in writing courses might contribute to the abysmal retention rates for these populations.

I don’t know these things partially because the secondary research doesn’t have much to say about them yet, or what is said is only provisional, out of date, or simply offers hints. It is partially for this reason that at the same time I’ve been doing this secondary research I have also begun my own primary research.

I have begun an IRB-approved study examining the history of disability service provision and disability policy in the CUNY system. Through a series of interviews and focus groups with current and former disability service providers, and by gathering and examining an archive of disability policy documents and service provider publications, I am attempting to study how disability politics and disability discourse have worked in real world institutions.

I am hoping that this research will move me out of the abstract realm of disability theory and into a practical understanding of how disability in higher education is affected by things like administrative policies and on-the-ground work by staff and faculty working in classrooms and boardrooms. I hope that I will discover insights from this research to help inform my work promoting access as as a progressive writing program administrator and activist scholar.

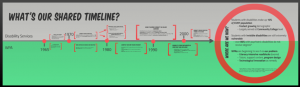

I will give just a few quick examples of the ways I’m trying to put my emerging expertise from this secondary and primary research to use. In March and July of last year, I gave presentations at national conferences arguing that writing teachers and WPAs have much to learn by better understanding the history of disability politics and inclusion on college campuses. I presented this timeline which synthesizes insights from all my research to re-present the history of progressive writing program theory, drawing new parallels to pushes for disability inclusion in higher education.  By contrasting the well-known history of writing-studies’s evolving approaches to student difference with the largely unknown history of disability activism and progressive inclusion in higher education, I hoped to help WPAs understand how current emerging interests in disability studies within composition/rhetoric represents not a disruption, but a culmination of our longstanding investments in social justice, diversity, and innovation.

By contrasting the well-known history of writing-studies’s evolving approaches to student difference with the largely unknown history of disability activism and progressive inclusion in higher education, I hoped to help WPAs understand how current emerging interests in disability studies within composition/rhetoric represents not a disruption, but a culmination of our longstanding investments in social justice, diversity, and innovation.

To those same audiences, I also presented some early findings from my interviews and archive gathering, showing how disability service provider work has direct application in the writing classroom and the work of WPAs. For instance, I described the work of Anthony Collarossi, a former disability director at Kingsborrough Community College. Collarossi–an LD specialist, a former school counselor, and a self-identified person with disabilities–developed training materials for instructors at his campus based on Multiple Intelligence theory and cognitive psychology research on different learning styles.  He also designed and piloted a set of credit-baring gateway courses for at-risk students both with and without diagnosed disabilities, courses that blended together academic support, self-advocacy, and multimodal writing instruction. Writing teachers and WPAs alike have been enthusiastic, and have easily understood the importance of recovering these kinds of disability-inspired innovations for potential application to our own practices.